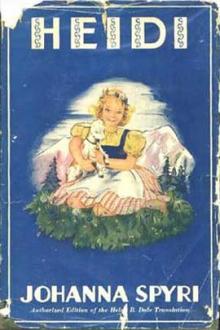

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

Rottenmeier had met her and scolded her on the steps, and told

her how wicked and ungrateful she was to try and run away, and

what a good thing it was that Herr Sesemann knew nothing about

it, a change had come over the child. She had at last understood

that day that she could not go home when she wished as Dete had

told her, but that she would have to stay on in Frankfurt for a

long, long time, perhaps for ever. She had also understood that

Herr Sesemann would think it ungrateful of her if she wished to

leave, and she believed that the grandmother and Clara would

think the same. So there was nobody to whom she dared confide

her longing to go home, for she would not for the world have

given the grandmother, who was so kind to her, any reason for

being as angry with her as Fraulein Rottenmeier had been. But the

weight of trouble on the little heart grew heavier and heavier;

she could no longer eat her food, and every day she grew a little

paler. She lay awake for long hours at night, for as soon as she

was alone and everything was still around her, the picture of

the mountain with its sunshine and flowers rose vividly before

her eyes; and when at last she fell asleep it was to dream of the

rocks and the snowfield turning crimson in the evening light,

and waking in the morning she would think herself back at the

hut and prepare to run joyfully out into—the sun—and then—

there was her large bed, and here she was in Frankfurt far, far

away from home. And Heidi would often lay her face down on the

pillow and weep long and quietly so that no one might hear her.

Heidi’s unhappiness did not escape the grandmother’s notice. She

let some days go by to see if the child grew brighter and lost

her down-cast appearance. But as matters did not mend, and she

saw that many mornings Heidi had evidently been crying before

she came downstairs, she took her again into her room one day,

and drawing the child to her said, “Now tell me, Heidi, what is

the matter; are you in trouble?”

But Heidi, afraid if she told the truth that the grandmother

would think her ungrateful, and would then leave off being so

kind to her, answered, “can’t tell you.”

“Well, could you tell Clara about it?”

“Oh, no, I cannot tell any one,” said Heidi in so positive a

tone, and with a look of such trouble on her face, that the

grandmother felt full of pity for the child.

“Then, dear child, let me tell you what to do: you know that

when we are in great trouble, and cannot speak about it to

anybody, we must turn to God and pray Him to help, for He can

deliver us from every care, that oppresses us. You understand

that, do you not? You say your prayers every evening to the dear

God in Heaven, and thank Him for all He has done for you, and

pray Him to keep you from all evil, do you not?”

“No, I never say any prayers,” answered Heidi.

“Have you never been taught to pray, Heidi; do you not know even

what it means?”

“I used to say prayers with the first grandmother, but that is a

long time ago, and I have forgotten them.”

“That is the reason, Heidi, that you are so unhappy, because you

know no one who can help you. Think what a comfort it is when

the heart is heavy with grief to be able at any moment to go and

tell everything to God, and pray Him for the help that no one

else can give us. And He can help us and give us everything that

will make us happy again.”

A sudden gleam of joy came into Heidi’s eyes. “May I tell Him

everything, everything?”

“Yes, everything, Heidi, everything.”

Heidi drew her hand away, which the grandmother was holding

affectionately between her own, and said quickly, “May I go?”

“Yes, of course,” was the answer, and Heidi ran out of the room

into her own, and sitting herself on a stool, folded her hands

together and told God about everything that was making her so

sad and unhappy, and begged Him earnestly to help her and to let

her go home to her grandfather.

It was about a week after this that the tutor asked Frau

Sesemann’s permission for an interview with her, as he wished to

inform her of a remarkable thing that had come to pass. So she

invited him to her room, and as he entered she held out her hand

in greeting, and pushing a chair towards him, “I am pleased to

see you,” she said, “pray sit down and tell me what brings you

here; nothing bad, no complaints, I hope?”

“Quite the reverse,” began the tutor. “Something has happened

that I had given up hoping for, and which no one, knowing what

has gone before, could have guessed, for, according to all

expectations, that which has taken place could only be looked

upon as a miracle, and yet it really has come to pass and in the

most extraordinary manner, quite contrary to all that one could

anticipate—”

“Has the child Heidi really learnt to read at last?” put in Frau

Sesemann.

The tutor looked at the lady in speechless astonishment. At last

he spoke again. “It is indeed truly marvellous, not only because

she never seemed able to learn her A B C even after all my full

explanations, and after spending unusual pains upon her, but

because now she has learnt it so rapidly, just after I had made

up my mind to make no further attempts at the impossible but to

put the letters as they were before her without any dissertation

on their origin and meaning, and now she has as you might say

learnt her letters over night, and started at once to read

correctly, quite unlike most beginners. And it is almost as

astonishing to me that you should have guessed such an unlikely

thing.”

“Many unlikely things happen in life,” said Frau Sesemann with a

pleased smile. “Two things coming together may produce a happy

result, as for instance, a fresh zeal for learning and a new

method of teaching, and neither does any harm. We can but

rejoice that the child has made such a good start and hope for

her future progress.”

After parting with the tutor she went down to the study to make

sure of the good news. There sure enough was Heidi, sitting

beside Clara and reading aloud to her, evidently herself very

much surprised, and growing more and more delighted with the new

world that was now open to her as the black letters grew alive

and turned into men and things and exciting stories. That same

evening Heidi found the large book with the beautiful pictures

lying on her plate when she took her place at table, and when

she looked questioningly at the grandmother, the latter nodded

kindly to her and said, “Yes, it’s yours now.”

“Mine, to keep always? even when I go home?” said, Heidi,

blushing with pleasure.

“Yes, of course, yours for ever,” the grandmother assured her.

“Tomorrow we will begin to read it.”

“But you are not going home yet, Heidi, not for years,” put in

Clara. “When grandmother goes away, I shall want you to stay on

with me.”

When, Heidi went to her room that night she had another look at

her book before going to bed, and from that day forth her chief

pleasure was to read the tales which belonged to the beautiful

pictures over and over again. If the grandmother said, as they

were sitting together in the evening, “Now Heidi will read aloud

to us,” Heidi was delighted, for reading was no trouble to her

now, and when she read the tales aloud the scenes seemed to grow

more beautiful and distinct, and then grandmother would explain

and tell her more about them still.

Still the picture she liked best was the one of the shepherd

leaning on his staff with his flock around him in the midst of

the green pasture, for he was now at home and happy, following

his father’s sheep and goats. Then came the picture where he was

seen far away from his father’s house, obliged to look after the

swine, and he had grown pale and thin from the husks which were

all he had to eat. Even the sun seemed here to be less bright

and everything looked grey and misty. But there was the third

picture still to this tale: here was the old father with

outstretched arms running to meet and embrace his returning and

repentant son, who was advancing timidly, worn out and emaciated

and clad in a ragged coat. That was Heidi’s favorite tale, which

she read over and over again, aloud and to herself, and she was

never tired of hearing the grandmother explain it to her and

Clara. But there were other tales in the book besides, and what

with reading and looking at the pictures the days passed quickly

away, and the time drew near for the grandmother to return home.

CHAPTER XI. HEIDI GAINS IN ONE WAY AND LOSES IN ANOTHER

Every afternoon during her visit the grandmother went and sat

down for a few minutes beside Clara after dinner, when the

latter was resting, and Fraulein Rottenmeier, probably for the

same reason, had disappeared inside her room; but five minutes

sufficed her, and then she was up again, and Heidi was sent for

to her room, and there she would talk to the child and employ

and amuse her in all sorts of ways. The grandmother had a lot of

pretty dolls, and she showed Heidi how to make dresses and

pinafores for them, so that Heidi learnt how to sew and to make

all sorts of beautiful clothes for the little people out of a

wonderful collection of pieces that grandmother had by her of

every describable and lovely color. And then grandmother liked

to hear her read aloud, and the oftener Heidi read her tales the

fonder she grew of them. She entered into the lives of all the

people she read about so that they became like dear friends to

her, and it delighted her more and more to be with them. But

still Heidi never looked really happy, and her bright eyes were

no longer to be seen. It was the last week of the grandmother’s

visit. She called Heidi into her room as usual one day after

dinner, and the child came with her book under her arm. The

grandmother called her to come close, and then laying the book

aside, said, “Now, child, tell me why you are not happy? Have

you still the same trouble at heart?”

Heidi nodded in reply.

“Have you told God about it?”

“Yes.”

“And do you pray every day that He will make things right and

that you may be happy again?”

“No, I have left off praying.”

“Do not tell me that, Heidi! Why have you left off praying?”

“It is of no use, God does not listen,” Heidi went on in an

agitated voice, “and I can understand that when there are so

many, many people in Frankfurt praying to Him every evening that

He cannot attend to them all, and He certainly has not heard

what I said to Him.”

“And why are you so sure of that, Heidi?”

Comments (0)