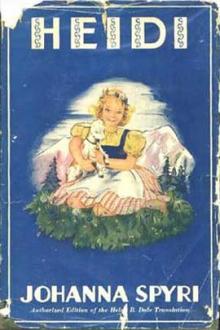

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

to unfasten, for Dete had put the Sunday frock on over the

everyday one, to save the trouble of carrying it. Quick as

lightning the everyday frock followed the other, and now the

child stood up, clad only in her light short-sleeved under

garment, stretching out her little bare arms with glee. She put

all her clothes together in a tidy little heap, and then went

jumping and climbing up after Peter and the goats as nimbly as

any one of the party. Peter had taken no heed of what the child

was about when she stayed behind, but when she ran up to him in

her new attire, his face broke into a grin, which grew broader

still as he looked back and saw the small heap of clothes lying

on the ground, until his mouth stretched almost from ear to ear;

he said nothing, however. The child, able now to move at her

ease, began to enter into conversation with Peter, who had many

questions to answer, for his companion wanted to know how many

goats he had, where he was going to with them, and what he had to

do when he arrived there. At last, after some time, they and the

goats approached the hut and came within view of Cousin Dete.

Hardly had the latter caught sight of the little company climbing

up towards her when she shrieked out: “Heidi, what have you been

doing! What a sight you have made of yourself! And where are your

two frocks and the red wrapper? And the new shoes I bought, and

the new stockings I knitted for you—everything gone! not a thing

left! What can you have been thinking of, Heidi; where are all

your clothes?”

The child quietly pointed to a spot below on the mountain side

and answered, “Down there.” Dete followed the direction of her

finger; she could just distinguish something lying on the

ground, with a spot of red on the top of it which she had no

doubt was the woollen wrapper.

“You good-for-nothing little thing!” exclaimed Dete angrily,

“what could have put it into your head to do like that? What

made you undress yourself? What do you mean by it?”

“I don’t want any clothes,” said the child, not showing any sign

of repentance for her past deed.

“You wretched, thoughtless child! have you no sense in you at

all?” continued Dete, scolding and lamenting. “Who is going all

that way down to fetch them; it’s a good half-hour’s walk!

Peter, you go off and fetch them for me as quickly as you can,

and don’t stand there gaping at me, as if you were rooted to the

ground!”

“I am already past my time,” answered Peter slowly, without

moving from the spot where he had been standing with his hands

in his pockets, listening to Dete’s outburst of dismay and anger.

“Well, you won’t get far if you only keep on standing there with

your eyes staring out of your head,” was Dete’s cross reply;

“but see, you shall have something nice,” and she held out a

bright new piece of money to him that sparkled in the sun. Peter

was immediately up and off down the steep mountain side, taking

the shortest cut, and in an incredibly short space of time had

reached the little heap of clothes, which he gathered up under

his arm, and was back again so quickly that even Dete was

obliged to give him a word of praise as she handed him the

promised money. Peter promptly thrust it into his pocket and his

face beamed with delight, for it was not often that he was the

happy possessor of such riches.

You can carry the things up for me as far as Uncle’s, as you are

going the same way,” went on Dete, who was preparing to continue

her climb up the mountain side, which rose in a steep ascent

immediately behind the goatherd’s hut. Peter willingly undertook

to do this, and followed after her on his bare feet, with his

left arm round the bundle and the right swinging his goatherd’s

stick, while Heidi and the goats went skipping and jumping

joyfully beside him. After a climb of more than three-quarters

of an hour they reached the top of the Alm mountain. Uncle’s hut

stood on a projection of the rock, exposed indeed to the winds,

but where every ray of sun could rest upon it, and a full view

could be had of the valley beneath. Behind the hut stood three

old fir trees, with long, thick, unlopped branches. Beyond these

rose a further wall of mountain, the lower heights still

overgrown with beautiful grass and plants, above which were

stonier slopes, covered only with scrub, that led gradually up

to the steep, bare rocky summits.

Against the hut, on the side looking towards the valley, Uncle

had put up a seat. Here he was sitting, his pipe in his mouth

and his hands on his knees, quietly looking out, when the

children, the goats and Cousin Dete suddenly clambered into view.

Heidi was at the top first. She went straight up to the old man,

put out her hand, and said, “Good-evening, Grandfather.”

“So, so, what is the meaning of this?” he asked gruffly, as he

gave the child an abrupt shake of the hand, and gazed long and

scrutinisingly at her from under his bushy eyebrows. Heidi

stared steadily back at him in return with unflinching gaze, for

the grandfather, with his long beard and thick grey eyebrows that

grew together over his nose and looked just like a bush, was

such a remarkable appearance, that Heidi was unable to take her

eyes off him. Meanwhile Dete had come up, with Peter after her,

and the latter now stood still a while to watch what was going

on.

“I wish you good-day, Uncle,” said Dete, as she walked towards

him, “and I have brought you Tobias and Adelaide’s child. You

will hardly recognise her, as you have never seen her since she

was a year old.”

“And what has the child to do with me up here?” asked the old

man curtly. “You there,” he then called out to Peter, “be off

with your goats, you are none too early as it is, and take mine

with you.”

Peter obeyed on the instant and quickly disappeared, for the old

man had given him a look that made him feel that he did not want

to stay any longer.

“The child is here to remain with you,” Dete made answer. “I

have, I think, done my duty by her for these four years, and now

it is time for you to do yours.”

“That’s it, is it?” said the old man, as he looked at her with a

flash in his eye. “And when the child begins to fret and whine

after you, as is the way with these unreasonable little beings,

what am I to do with her then?”

“That’s your affair,” retorted Dete. “I know I had to put up

with her without complaint when she was left on my hands as an

infant, and with enough to do as it was for my mother and self.

Now I have to go and look after my own earnings, and you are the

next of kin to the child. If you cannot arrange to keep her, do

with her as you like. You will be answerable for the result if

harm happens to her, though you have hardly need, I should think,

to add to the burden already on your conscience.”

Now Dete was not quite easy in her own conscience about what she

was doing, and consequently was feeling hot and irritable, and

said more than she had intended. As she uttered her last words,

Uncle rose from his seat. He looked at her in a way that made

her draw back a step or two, then flinging out his arm, he said

to her in a commanding voice: “Be off with you this instant, and

get back as quickly as you can to the place whence you came, and

do not let me see your face again in a hurry.”

Dete did not wait to be told twice. “Good-bye to you then, and

to you too, Heidi,” she called, as she turned quickly away and

started to descend the mountain at a running pace, which she did

not slacken till she found herself safely again at Dorfli, for

some inward agitation drove her forwards as if a steam-engine

was at work inside her. Again questions came raining down upon

her from all sides, for every one knew Dete, as well as all

particulars of the birth and former history of the child, and

all wondered what she had done with it. From every door and

window came voices calling: “Where is the child?” “Where have you

left the child, Dete?” and more and more reluctantly Dete made

answer, “Up there with Alm-Uncle!” “With Alm-Uncle, have I not

told you so already?”

Then the women began to hurl reproaches at her; first one cried

out, “How could you do such a thing!” then another, “To think of

leaving a helpless little thing up there,”—while again and

again came the words, “The poor mite! the poor mite!” pursuing

her as she went along. Unable at last to bear it any longer Dete

ran forward as fast as she could until she was beyond reach of

their voices. She was far from happy at the thought of what she

had done, for the child had been left in her care by her dying

mother. She quieted herself, however, with the idea that she

would be better able to do something for the child if she was

earning plenty of money, and it was a relief to her to think

that she would soon be far away from all these people who were

making such a fuss about the matter, and she rejoiced further

still that she was at liberty now to take such a good place.

CHAPTER II. AT HOME WITH GRANDFATHER

As soon as Dete had disappeared the old man went back to his

bench, and there he remained seated, staring on the ground

without uttering a sound, while thick curls of smoke floated

upward from his pipe. Heidi, meanwhile, was enjoying herself in

her new surroundings; she looked about till she found a shed,

built against the hut, where the goats were kept; she peeped in,

and saw it was empty. She continued her search and presently

came to the fir trees behind the hut. A strong breeze was blowing

through them, and there was a rushing and roaring in their

topmost branches, Heidi stood still and listened. The sound

growing fainter, she went on again, to the farther corner of the

hut, and so round to where her grandfather was sitting. Seeing

that he was in exactly the same position as when she left him,

she went and placed herself in front of the old man, and putting

her hands behind her back, stood and gazed at him. Her

grandfather looked up, and as she continued standing there

without moving, “What is it you want?” he asked.

“I want to see what you have inside the house,” said Heidi.

“Come then!” and the grandfather rose and went before her

towards the hut.

“Bring your bundle of clothes in with you,” he bid her as she

was following.

“I shan’t want them any more,” was her prompt answer.

The old man turned and looked searchingly at the child, whose

dark eyes were sparkling in delighted anticipation of what she

was going to see inside. “She is certainly not wanting in

intelligence,” he murmured to himself. “And why shall you

Comments (0)