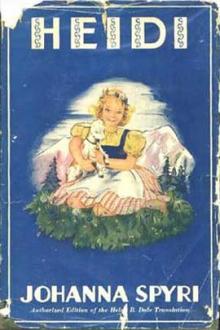

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

feel quite like home. Alm-Uncle, on his side, greatly regretted

the departure of his guest, and Heidi had been now accustomed

for so long to see her good friend every day that she could

hardly believe the time had suddenly come to separate. She looked

up at him in doubt, taken by surprise, but there was no help, he

must go. So he bid farewell to the old man and asked that Heidi

might go with him part of the return way, and Heidi took his hand

and went down the mountain with him, still unable to grasp the

idea that he was going for good. After some distance the doctor

stood still, and passing his hand over the child’s curly head

said, “Now, Heidi, you must go back, and I must say good-bye! If

only I could take you with me to Frankfurt and keep you there!”

The picture of Frankfurt rose before the child’s eyes, its rows

of endless houses, its hard streets, and even the vision of

Fraulein Rottenmeier and Tinette, and she answered hesitatingly,

“I would rather that you came back to us.”

“Yes, you are right, that would be better. But now good-bye,

Heidi.” The child put her hand in his and looked up at him; the

kind eyes looking down on her had tears in them. Then the doctor

tore himself away and quickly continued his descent.

Heidi remained standing without moving. The friendly eyes with

the tears in them had gone to her heart. All at once she burst

into tears and started running as fast as she could after the

departing figure, calling out in broken tones: “Doctor! doctor!”

He turned round and waited till the child reached him. The tears

were streaming down her face and she sobbed out: “I will come to

Frankfurt with you, now at once, and I will stay with you as

long as you like, only I must just run back and tell

grandfather.”

The doctor laid his hand on her and tried to calm her

excitement. “No, no, dear child,” he said kindly, “not now; you

must stay for the present under the fir trees, or I should have

you ill again. But hear now what I have to ask you. If I am ever

ill and alone, will you come then and stay with me? May I know

that there would then be some one to look after me and care for

me?”

“Yes, yes, I will come the very day you send for me, and I love

you nearly as much as grandfather,” replied Heidi, who had not

yet got over her distress.

And so the doctor again bid her good-bye and started on his way,

while Heidi remained looking after him and waving her hand as

long as a speck of him could be seen. As the doctor turned for

the last time and looked back at the waving Heidi and the sunny

mountain, he said to himself, “It is good to be up there, good

for body and soul, and a man might learn how to be happy once

more.”

CHAPTER XVIII. WINTER IN DORFLI

The snow was lying so high around the hut that the windows

looked level with the ground, and the door had entirely

disappeared from view. If Alm-Uncle had been up there he would

have had to do what Peter did daily, for fresh snow fell every

night. Peter had to get out of the window of the sitting-room

every morning, and if the frost had not been very hard during the

night, he immediately sank up to his shoulders almost in the snow

and had to struggle with hands, feet, and head to extricate

himself. Then his mother handed him the large broom, and with

this he worked hard to make a way to the door. He had to be

careful to dig the snow well away, or else as soon as the door

was opened the whole soft mass would fall inside, or, if the

frost was severe enough, it would have made such a wall of ice in

front of the house that no one could have gone in or out, for the

window was only big enough for Peter to creep through. The fresh

snow froze like this in the night sometimes, and this was an

enjoyable time for Peter, for he would get through the window on

to the hard, smooth, frozen ground, and his mother would hand him

out the little sleigh, and he could then make his descent to

Dorfli along any route he chose, for the whole mountain was

nothing but one wide, unbroken sleigh road.

Alm-Uncle had kept his word and was not spending the winter in

his old home. As soon as the first snow began to fall, he had

shut up the hut and the outside buildings and gone down to

Dorfli with Heidi and the goats. Near the church was a straggling

half-ruined building, which had once been the house of a person

of consequence. A distinguished soldier had lived there at one

time; he had taken service in Spain and had there performed many

brave deeds and gathered much treasure. When he returned home to

Dorfli he spent part of his booty in building a fine house, with

the intention of living in it. But he had been too long

accustomed to the noise and bustle of arms and the world to care

for a quiet country life, and he soon went off again, and this

time did not return. When after many long years it seemed

certain that he was dead, a distant relative took possession of

the house, but it had already fallen into disrepair, and he had

no wish to rebuild it. So it was let to poor people, who paid but

a small rent, and when any part of the building fell it was

allowed to remain. This had now gone on for many years. As long

ago as when his son Tobias was a child Alm-Uncle had rented the

tumble-down old place. Since then it had stood empty, for no one

could stay in it who had not some idea of how to stop up the

holes and gaps and make it habitable. Otherwise the wind and rain

and snow blew into the rooms, so that it was impossible even to

keep a candle alight, and the indwellers would have been frozen

to death during the long cold winters. Alm-Uncle, however, knew

how to mend matters. As soon as he made up his mind to spend the

winter in Dorfli, he rented the old place and worked during the

autumn to get it sound and tight. In the middle of October he and

Heidi took up their residence there.

On approaching the house from the back one came first into an

open space with a wall on either side, of which one was half in

ruins. Above this rose the arch of an old window thickly

overgrown with ivy, which spread over the remains of a domed

roof that had evidently been part of a chapel. A large hall came

next, which lay open, without doors, to the square outside. Here

also walls and roof only partially remained, and indeed what was

left of the roof looked as if it might fall at any minute had it

not been for two stout pillars that supported it. Alm-Uncle had

here put up a wooden partition and covered the floor with straw,

for this was to be the goats’ house. Endless passages led from

this, through the rents of which the sky as well as the fields

and the road outside could be seen at intervals; but at last one

came to a stout oak door that led into a room that still stood

intact. Here the walls and the dark wainscoting remained as good

as ever, and in the corner was an immense stove reaching nearly

to the ceiling, on the white tiles of which were painted large

pictures in blue. These represented old castles surrounded with

trees, and huntsmen riding out with their hounds; or else a quiet

lake scene, with broad oak trees and a man fishing. A seat ran

all round the stove so that one could sit at one’s ease and study

the pictures. These attracted Heidi’s attention at once, and she

had no sooner arrived with her grandfather than she ran and

seated herself and began to examine them. But when she had

gradually worked herself round to the back, something else

diverted her attention. In the large space between the stove and

the wall four planks had been put together as if to make a large

receptacle for apples; there were no apples, however, inside, but

something Heidi had no difficulty in recognising, for it was her

very own bed, with its hay mattress and sheets, and sack for a

coverlid, just as she had it up at the hut. Heidi clapped her

hands for joy and exclaimed, “O grandfather, this is my room, how

nice! But where are you going to sleep?”

“Your room must be near the stove or you will freeze,” he

replied, “but you can come and see mine too.”

Heidi got down and skipped across the large room after her

grandfather, who opened a door at the farther end leading into a

smaller one which was to be his bedroom. Then came another door.

Heidi pushed it open and stood amazed, for here was an immense

room like a kitchen, larger than anything of the kind that Heidi

had seen before. There was still plenty of work for the

grandfather before this room could be finished, for there were

holes and cracks in the walls through which the wind whistled,

and yet he had already nailed up so many new planks that it

looked as if a lot of small cupboards had been set up round the

room. He had, however, made the large old door safe with many

screws and nails, as a protection against the outside air, and

this was very necessary, for just beyond was a mass of ruined

buildings overgrown with tall weeds, which made a dwelling-place

for endless beetles and lizards.

Heidi was very delighted with her new home, and by the morning

after their arrival she knew every nook and corner so thoroughly

that she could take Peter over it and show him all that was to

be seen; indeed she would not let him go till he had examined

every single wonderful thing contained in it.

Heidi slept soundly in her corner by the stove; but every

morning when she first awoke she still thought she was on the

mountain, and that she must run outside at once to see if the fir

trees were so quiet because their branches were weighed down with

the thick snow. She had to look about her for some minutes before

she felt quite sure where she was, and a certain sensation of

trouble and oppression would come over her as she grew aware that

she was not at home in the hut. But then she would hear her

grandfather’s voice outside, attending to the goats, and these

would give one or two loud bleats, as if calling to her to make

haste and go to them, and then Heidi was happy again, for she

knew she was still at home, and she would jump gladly out of bed

and run out to the animals as quickly as she could. On the fourth

morning, as soon as she saw her grandfather, she said, “I must go

up to see grandmother to-day; she ought not to be alone so long.”

But the grandfather would not agree to this. “Neither to-day nor

tomorrow can you go,” he said; “the mountain is covered fathom-deep in snow, and the snow is still

Comments (0)