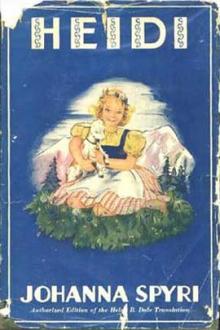

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

All the gentlemen in Frankfurt with tall black hats on their

heads, and scorn and mockery in their faces rose up before his

mind’s eye, and he threw himself with energy on the Y, not

letting it go till at last he knew it so thoroughly that he

could see what it was like even when he shut his eyes.

He arrived on the following day in a somewhat lofty frame of

mind, for there was now only one letter to struggle over, and

when Heidi began the lesson with reading aloud:—

Make haste with Z, if you’re too slow Off to the

Hottentots you’ll go.

Peter remarked scornfully, “I dare say, when no one knows even

where such people live.”

“I assure you, Peter,” replied Heidi, “grandfather knows all

about them. Wait a second and I will run and ask him, for he is

only over the way with the pastor.” And she rose and ran to the

door to put her words into action, but Peter cried out in a

voice of agony,—

“Stop!” for he already saw himself being carried off by Alm-Uncle and the pastor and sent straight away to the Hottentots,

since as yet he did not know his last letter. His cry of fear

brought Heidi back.

“What is the matter?” she asked in astonishment.

“Nothing! come back! I am going to learn my letter,” he said,

stammering with fear. Heidi, however, herself wished to know

where the Hottentots lived and persisted that she should ask her

grandfather, but she gave in at last to Peter’s despairing

entreaties. She insisted on his doing something in return, and

so not only had he to repeat his Z until it was so fixed in his

memory that he could never forget it again, but she began

teaching him to spell, and Peter really made a good start that

evening. So it went on from day to day.

The frost had gone and the snow was soft again, and moreover

fresh snow continually fell, so that it was quite three weeks

before Heidi could go to the grandmother again. So much the more

eagerly did she pursue her teaching so that Peter might

compensate for her absence by reading hymns to the old woman.

One evening he walked in home after leaving Heidi, and as he

entered he said, “I can do it now.”

“Do what, Peter?” asked his mother.

“Read,” he answered.

“Do you really mean it? Did you hear that, grandmother?” she

called out.

The grandmother had heard, and was already wondering how such a

thing could have come to pass.

“I must read one of the hymns now; Heidi told me to,” he went on

to inform them. His mother hastily fetched the book, and the

grandmother lay in joyful expectation, for it was so long since

she had heard the good words. Peter sat down to the table and

began to read. His mother sat beside him listening with surprise

and exclaiming at the close of each verse, “Who would have

thought it possible!”

The grandmother did not speak though she followed the words he

read with strained attention.

It happened on the day following this that there was a reading

lesson in Peter’s class. When it came to his turn, the teacher

said,—

“We must pass over Peter as usual, or will you try again once

more—I will not say to read, but to stammer through a

sentence.”

Peter took the book and read off three lines without the

slightest hesitation.

The teacher put down his book and stared at Peter as at some out-of-the-way and marvellous thing unseen before. At last he spoke,—

“Peter, some miracle has been performed upon you! Here have I

been striving with unheard-of patience to teach you and you have

not hitherto been able to say your letters even. And now, just

as I had made up my mind not to waste any more trouble upon you,

you suddenly are able to read a consecutive sentence properly and

distinctly. How has such a miracle come to pass in our days?”

“It was Heidi,” answered Peter.

The teacher looked in astonishment towards Heidi, who was

sitting innocently on her bench with no appearance of anything

supernatural about her. He continued, “I have noticed a change

in you altogether, Peter. Whereas formerly you often missed

coming to school for a week, or even weeks at a time, you have

lately not stayed away a single day. Who has wrought this change

for good in you?”

“It was Uncle,” answered Peter.

With increasing surprise the teacher looked from Peter to Heidi

and back again at Peter.

“We will try once more,” he said cautiously, and Peter had again

to show off his accomplishment by reading another three lines.

There was no mistake about it—Peter could read. As soon as

school was over the teacher went over to the pastor to tell him

this piece of news, and to inform him of the happy result of

Heidi’s and the grandfather’s combined efforts.

Every evening Peter read one hymn aloud; so far he obeyed Heidi.

Nothing would induce him to read a second, and indeed the

grandmother never asked for it. His mother Brigitta could not

get over her surprise at her son’s attainment, and when the

reader was in bed would often express her pleasure at it. “Now he

has learnt to read there is no knowing what may be made of him

yet.”

On one of these occasions the grandmother answered, “Yes, it is

good for him to have learnt something, but I shall indeed be

thankful when spring is here again and Heidi can come; they are

not like the same hymns when Peter reads them. So many words

seem missing, and I try to think what they ought to be and then I

lose the sense, and so the hymns do not come home to my heart as

when Heidi reads them.”

The truth was that Peter arranged to make his reading as little

troublesome for himself as possible. When he came upon a word

that he thought was too long or difficult in any other way, he

left it out, for he decided that a word or two less in a verse,

where there were so many of them, could make no difference to

his grandmother. And so it came about that most of the principal

words were missing in the hymns that Peter read aloud.

CHAPTER XX. NEWS FROM DISTANT FRIENDS

It was the month of May. From every height the full fresh

streams of spring were flowing down into the valley. The clear

warm sunshine lay upon the mountain, which had turned green

again. The last snows had disappeared and the sun had already

coaxed many of the flowers to show their bright heads above the

grass. Up above the gay young wind of spring was singing through

the fir trees, and shaking down the old dark needles to make room

for the new bright green ones that were soon to deck out the

trees in their spring finery. Higher up still the great bird went

circling round in the blue ether as of old, while the golden

sunshine lit up the grandfather’s hut, and all the ground about

it was warm and dry again so that one might sit out where one

liked. Heidi was at home again on the mountain, running backwards

and forwards in her accustomed way, not knowing which spot was

most delightful. Now she stood still to listen to the deep,

mysterious voice of the wind, as it blew down to her from the

mountain summits, coming nearer and nearer and gathering strength

as it came, till it broke with force against the fir trees,

bending and shaking them, and seeming to shout for joy, so that

she too, though blown about like a feather, felt she must join in

the chorus of exulting sounds. Then she would run round again to

the sunny space in front of the hut, and seating herself on the

ground would peer closely into the short grass to see how many

little flower cups were open or thinking of opening. She rejoiced

with all the myriad little beetles and winged insects that jumped

and crawled and danced in the sun, and drew in deep draughts of

the spring scents that rose from the newly-awakened earth, and

thought the mountain was more beautiful than ever. All the tiny

living creatures must be as happy as she, for it seemed to her

there were little voices all round her singing and humming in

joyful tones, “On the mountain! on the mountain!”

From the shed at the back came the sound of sawing and chopping,

and Heidi listened to it with pleasure, for it was the old

familiar sound she had known from the beginning of her life up

here. Suddenly she jumped up and ran round, for she must know

what her grandfather was doing. In front of the shed door

already stood a finished new chair, and a second was in course of

construction under the grandfather’s skilful hand.

“Oh, I know what these are for,” exclaimed Heidi in great glee.

“We shall want them when they all come from Frankfurt. This one

is for Grandmamma, and the one you are now making is for Clara,

and then—then, there will, I suppose, have to be another,”

continued Heidi with more hesitation in her voice, “or do you

think, grandfather, that perhaps Fraulein Rottenmeier will not

come with them?”

“Well, I cannot say just yet,” replied her grandfather, “but it

will be safer to make one so that we can offer her a seat if she

does.”

Heidi looked thoughtfully at the plain wooden chair without arms

as if trying to imagine how Fraulein Rottenmeier and a chair of

this sort would suit one another. After a few minutes’

contemplation, “Grandfather,” she said, shaking her head

doubtfully, “I don’t think she would be able to sit on that.”

“Then we will invite her on the couch with the beautiful green

turf feather-bed,” was her grandfather’s quiet rejoinder.

While Heidi was pausing to consider what this might be there

approached from above a whistling, calling, and other sounds

which Heidi immediately recognised. She ran out and found

herself surrounded by her four-footed friends. They were

apparently as pleased as she was to be among the heights again,

for they leaped about and bleated for joy, pushing Heidi this way

and that, each anxious to express his delight with some sign of

affection. But Peter sent them flying to right and left, for he

had something to give to Heidi. When he at last got up to her he

handed her a letter.

“There!” he exclaimed, leaving the further explanation of the

matter to Heidi herself.

“Did some one give you this while you were out with the goats,”

she asked, in her surprise.

“No,” was the answer.

“Where did you get it from then?

“I found it in the dinner bag.”

Which was true to a certain extent. The letter to Heidi had been

given him the evening before by the postman at Dorfli, and Peter

had put it into his empty bag. That morning he had stuffed his

bread and cheese on the top of it, and had forgotten it when he

fetched Alm-Uncle’s two goats; only when he had finished his

bread and cheese at mid-day and was searching in the bag for any

last crumbs did he remember the letter which lay at the bottom.

Heidi read the address carefully; then she ran back to the shed

holding out her letter to her grandfather in high glee. “From

Frankfurt!

Comments (0)