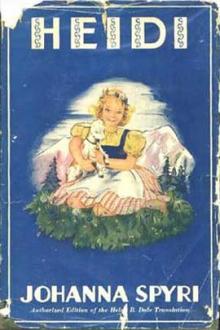

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

hardly get along. A little creature like you would soon be

smothered by it, and we should not be able to find you again.

Wait a bit till it freezes, then you will be able to walk over

the hard snow.”

Heidi did not like the thought of having to wait, but the days

were so busy that she hardly knew how they went by.

Heidi now went to school in Dorfli every morning and afternoon,

and eagerly set to work to learn all that was taught her. She

hardly ever saw Peter there, for as a rule he was absent. The

teacher was an easy-going man who merely remarked now and then,

“Peter is not turning up to-day again, it seems, but there is a

lot of snow up on the mountain and I daresay he cannot get

along.” Peter, however, always seemed able to make his way

through the snow in the evening when school was over, and he

then generally paid Heidi a visit.

At last, after some days, the sun again appeared and shone

brightly over the white ground, but he went to bed again behind

the mountains at a very early hour, as if he did not find such

pleasure in looking down on the earth as when everything was

green and flowery. But then the moon came out clear and large

and lit up the great white snowfield all through the night, and

the next morning the whole mountain glistened and sparkled like a

huge crystal. When Peter got out of his window as usual, he was

taken by surprise, for instead of sinking into the soft snow he

fell on the hard ground and went sliding some way down the

mountain side like a sleigh before he could stop himself. He

picked himself up and tested the hardness of the ground by

stamping on it and trying with all his might to dig his heels

into it, but even then he could not break off a single little

splinter of ice; the Alm was frozen hard as iron. This was just

what Peter had been hoping for, as he knew now that Heidi would

be able to come up to them. He quickly got back into the house,

swallowed the milk which his mother had put ready for him,

thrust a piece of bread in his pocket, and said, “I must be off

to school.” “That’s right, go and learn all you can,” said the

grandmother encouragingly. Peter crept through the window again—

the door was quite blocked by the frozen snow outside—pulling

his little sleigh after him, and in another minute was shooting

down the mountain.

He went like lightning, and when he reached Dorfli, which stood

on the direct road to Mayenfeld, he made up his mind to go on

further, for he was sure he could not stop his rapid descent

without hurting himself and the sleigh too. So down he still

went till he reached the level ground, where the sleigh came to a

pause of its own accord. Then he got out and looked round. The

impetus with which he had made his journey down had carried him

some little way beyond Mayenfeld. He bethought himself that it

was too late to get to school now, as lessons would already have

begun, and it would take him a good hour to walk back to Dorfli.

So he might take his time about returning, which he did, and

reached Dorfli just as Heidi had got home from school and was

sitting at dinner with her grandfather. Peter walked in, and as

on this occasion he had something particular to communicate, he

began without a pause, exclaiming as he stood still in the

middle of the room, “She’s got it now.”

“Got it? what?” asked the Uncle. “Your words sound quite

warlike, general.”

“The frost,” explained Peter.

“Oh! then now I can go and see grandmother!” said Heidi

joyfully, for she had understood Peter’s words at once. “But why

were you not at school then? You could have come down in the

sleigh,” she added reproachfully, for it did not agree with

Heidi’s ideas of good behavior to stay away when it was possible

to be there.

“It carried me on too far and I was too late,” Peter replied.

“I call that being a deserter,” said the Uncle, “and deserters

get their ears pulled, as you know.”

Peter gave a tug to his cap in alarm, for there was no one of

whom he stood in so much awe as Alm-Uncle.

“And an army leader like yourself ought to be doubly ashamed of

running away,” continued Alm-Uncle. “What would you think of

your goats if one went off this way and another that, and refused

to follow and do what was good for them? What would you do then?”

“I should beat them,” said Peter promptly.

“And if a boy behaved like these unruly goats, and he got a

beating for it, what would you say then?”

“Serve him right,” was the answer.

“Good, then understand this: next time you let your sleigh carry

you past the school when you ought to be inside at your lessons,

come on to me afterwards and receive what you deserve.”

Peter now understood the drift of the old man’s questions and

that he was the boy who behaved like the unruly goats, and he

looked somewhat fearfully towards the corner to see if anything

happened to be there such as he used himself on such occasions

for the punishment of his animals.

But now the grandfather suddenly said in a cheerful voice, “Come

and sit down and have something, and afterwards Heidi shall go

with you. Bring her back this evening and you will find supper

waiting for you here.”

This unexpected turn of conversation set Peter grinning all over

with delight. He obeyed without hesitation and took his seat

beside Heidi. But the child could not eat any more in her

excitement at the thought of going to see grandmother. She

pushed the potatoes and toasted cheese which still stood on her

plate towards him while Uncle was filling his plate from the

other side, so that he had quite a pile of food in front of him,

but he attacked it without any lack of courage. Heidi ran to the

cupboard and brought out the warm cloak Clara had sent her; with

this on and the hood drawn over her head, she was all ready for

her journey. She stood waiting beside Peter, and as soon as his

last mouthful had disappeared she said, “Come along now.” As the

two walked together Heidi had much to tell Peter of her two

goats that had been so unhappy the first day in their new stall

that they would not eat anything, but stood hanging their heads,

not even rousing themselves to bleat. And when she asked her

grandfather the reason of this, he told her it was with them as

with her in Frankfurt, for it was the first time in their lives

they had come down from the mountain. “And you don’t know what

that is, Peter, unless you have felt it yourself,” added Heidi.

The children had nearly reached their destination before Peter

opened his mouth; he appeared to be so sunk in thought that he

hardly heard what was said to him. As they neared home, however,

he stood still and said in a somewhat sullen voice, “I had

rather go to school even than get what Uncle threatened.”

Heidi was of the same mind, and encouraged him in his good

intention. They found Brigitta sitting alone knitting, for the

grandmother was not very well and had to stay the day in bed on

account of the cold. Heidi had never before missed the old

figure in her place in the corner, and she ran quickly into the

next room. There lay grandmother on her little poorly covered

bed, wrapped up in her warm grey shawl.

“Thank God,” she exclaimed as Heidi came running in; the poor

old woman had had a secret fear at heart all through the autumn,

especially if Heidi was absent for any length of time, for Peter

had told her of a strange gentleman who had come from Frankfurt,

and who had gone out with them and always talked to Heidi, and

she had felt sure he had come to take her away again. Even when

she heard he had gone off alone, she still had an idea that a

messenger would be sent over from Frankfurt to fetch the child.

Heidi went up to the side of the bed and said, “Are you very

ill, grandmother?”

“No, no, child,” answered the old woman reassuringly, passing

her hand lovingly over the child’s head, “It’s only the frost

that has got into my bones a bit.”

“Shall you be quite well then directly it turns warm again?”

“Yes, God willing, or even before that, for I want to get back

to my spinning; I thought perhaps I should do a little to-day,

but tomorrow I am sure to be all right again.” The old woman had

detected that Heidi was frightened and was anxious to set her

mind at ease.

Her words comforted Heidi, who had in truth been greatly

distressed, for she had never before seen the grandmother ill in

bed. She now looked at the old woman seriously for a minute or

two, and then said, “In Frankfurt everybody puts on a shawl to

go out walking; did you think it was to be worn in bed,

grandmother?”

“I put it on, dear child, to keep myself from freezing, and I am

so pleased with it, for my bedclothes are not very thick,” she

answered.

“But, grandmother,” continued Heidi, “your bed is not right,

because it goes downhill at your head instead of uphill.”

“I know it, child, I can feel it,” and the grandmother put up

her hand to the thin flat pillow, which was little more than a

board under her head, to make herself more comfortable; “the

pillow was never very thick, and I have lain on it now for so

many years that it has grown quite flat.”

“Oh, if only I had asked Clara to let me take away my Frankfurt

bed,” said Heidi. “I had three large pillows, one above the

other, so that I could hardly sleep, and I used to slip down to

try and find a flat place, and then I had to pull myself up

again, because it was proper to sleep there like that. Could you

sleep like that, grandmother?”

“Oh, yes! the pillows keep one warm, and it is easier to breathe

when the head is high,” answered the grandmother, wearily

raising her head as she spoke as if trying to find a higher

resting-place. “But we will not talk about that, for I have so

much that other old sick people are without for which I thank

God; there is the nice bread I get every day, and this warm

wrap, and your visits, Heidi. Will you read me something to-day?”

Heidi ran into the next room to fetch the hymn book. Then she

picked out the favorite hymns one after another, for she knew

them all by heart now, as pleased as the grandmother to hear

them again after so many days. The grandmother lay with folded

hands, while a smile of peace stole over the worn, troubled face,

like one to whom good news has been brought.

Suddenly Heidi paused. “Grandmother, are you feeling quite well

again already?”

“Yes, child, I have grown better while listening to you; read it

to the end.”

The child read on, and

Comments (0)