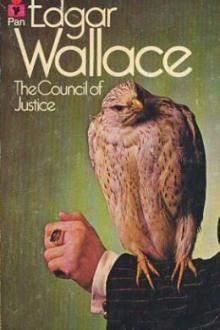

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

tolerate you.’

Poiccart was listening intently now.

‘These people demonstrate—Peter is really well off, with heaps of

slum property, and he has lured other wealthy ladies and gentlemen into

the movement. They demonstrate on all occasions. They have

chants—Peter calls them “chants”, and it is a nice distinction,

stamping them as it does with the stamp of semi-secularity—for these

festive moments, chants for the confusion of vaccinators, and eaters of

beasts, and such. But of all their “Services of Protest”

none is more thorough, more beautifully complete, than that which is

specially arranged to express their horror and abhorrence of capital

punishment.’

His pause was so long that Poiccart interjected an impatient—

‘Well?’

‘I was trying to think of the chant,’ said Leon thoughtfully. ‘If I

remember right one verse goes—

Come fight the gallant fight,

This horror to undo;

Two blacks will never make a white,

Nor legal murder too.

‘The last line,’ said Gonsalez tolerantly, ‘is a trifle vague, but

it conveys with delicate suggestion the underlying moral of the poem.

There is another verse which has for the moment eluded me, but perhaps

I shall think of it later.’

He sat up suddenly and leant over, dropping his hand on Poiccart’s

arm.

‘When we were talking of—our plan the other day you spoke of our

greatest danger, the one thing we could not avoid. Does it not seem to

you that the “Rational Faithers” offer a solution with their querulous

campaigns, their demonstrations, their brassy brass band, and their

preposterous chants?’

Poiccart pulled steadily at his pipe.

‘You’re a wonderful man, Leon,’ he said.

Leon walked over to the cupboard, unlocked it, and drew out a big

portfolio such as artists use to carry their drawings in. He untied the

strings and turned over the loose pages. It was a collection that had

cost the Four Just Men much time and a great deal of money.

‘What are you going to do?’ asked Poiccart, as the other, slipping

off his coat and fixing his pince-nez, sat down before a big plan he

had extracted from the portfolio. Leon took up a fine drawing-pen from

the table, examined the nib with the eye of a skilled craftsman, and

carefully uncorked a bottle of architect’s ink.

‘Have you ever felt a desire to draw imaginary islands?’ he asked,

‘naming your own bays, christening your capes, creating towns with a

scratch of your pen, and raising up great mountains with herringbone

“strokes? Because I’m going to do something like that—I feel in

that mood which in little boys is eloquently described as

“trying”, and I have the inclination to annoy Scotland Yard.’

It was the day before the trial that Falmouth made the discovery. To

be exact it was made for him. The keeper of a Gower Street boarding

house reported that two mysterious men had engaged rooms. They came

late at night with one portmanteau bearing divers foreign labels; they

studiously kept their faces in the shadow, and the beard of one was

obviously false. In addition to which they paid for their lodgings in

advance, and that was the most damning circumstance of all. Imagine

mine host, showing them to their rooms, palpitating with his tremendous

suspicion, calling to the full upon his powers of simulation,

ostentatiously nonchalant, and impatient to convey the news to the

police-station round the corner. For one called the other Leon, and

they spoke despairingly in stage whispers of ‘poor Manfred’.

They went out together, saying they would return soon after

midnight, ordering a fire for their bedroom, for the night was wet and

chilly.

Half an hour later the full story was being told to Falmouth over

the telephone.

‘It’s too good to be true,’ was his comment, but gave orders. The

hotel was well surrounded by midnight, but so skilfully that the casual

passer-by would never have suspected it. At three in the morning,

Falmouth decided that the men had been warned, and broke open their

doors to search the rooms. The portmanteau was their sole find. A few

articles of clothing, bearing the ‘tab’ of a Parisian tailor, was all

they found till Falmouth, examining the bottom of the portmanteau,

found that it was false.

‘Hullo!’ he said, and in the light of his discovery the exclamation

was modest in its strength, for, neatly folded, and cunningly hidden,

he came upon the plans. He gave them a rapid survey and whistled. Then

he folded them up and put them carefully in his pocket.

‘Keep the house under observation,’ he ordered. ‘I don’t expect

they’ll return, but if they do, take ‘em.’

Then he flew through the deserted streets as fast as a motor-car

could carry him, and woke the chief commissioner from a sound

sleep.

‘What is it?’ he asked as he led the detective to his study.

Falmouth showed him the plans.

The commissioner raised his eyebrows, and whistled.

‘That’s what I said,’ confessed Falmouth.

The chief spread the plans upon the big table.

‘Wandsworth, Pentonville and Reading,’ said the commissioner,

‘Plans, and remarkably good plans, of all three prisons.’

Falmouth indicated the writing in the cramped hand and the carefully

ruled lines that had been drawn in red ink.

‘Yes, I see them,’ said the commissioner, and read ‘“Wall 3

feet thick—dynamite here, warder on duty here—can be shot from wall,

distance to entrance to prison hall 25 feet; condemned cell here, walls

3 feet, one window, barred 10 feet 3 inches from ground”.’

‘They’ve got the thing down very fine—what is this—

Wandsworth?’

‘It’s the same with the others, sir,’ said Falmouth. ‘They’ve got

distances, heights and posts worked out; they must have taken years to

get this information.’

‘One thing is evident,’ said the commissioner; ‘they’ll do nothing

until after the trial—all these plans have been drawn with the

condemned cell as the point of objective.’

Next morning Manfred received a visit from Falmouth.

‘I have to tell you, Mr. Manfred,’ he said, ‘that we have in our

possession full details of your contemplated rescue.’

Manfred looked puzzled.

‘Last night your two friends escaped by the skin of their teeth,

leaving behind them elaborate plans—’

‘In writing?’ asked Manfred, with his quick smile.

‘In writing,’ said Falmouth solemnly. ‘I think it is my duty to tell

you this, because it seems that you are building too much upon what is

practically an impossibility, an escape from gaol.’

‘Yes,’ answered Manfred absently, ‘perhaps so—in writing I think

you said.’

‘Yes, the whole thing was worked out’—he thought he had said quite

enough, and turned the subject. ‘Don’t you think you ought to change

your mind and retain a lawyer?’

‘I think you’re right,’ said Manfred slowly. ‘Will you arrange for a

member of some respectable firm of solicitors to see me?’

‘Certainly,’ said Falmouth, ‘though you’ve left your defence—’

‘Oh, it isn’t my defence,’ said Manfred cheerfully; ‘only I think I

ought to make a will.’

CHAPTER XIV. At the Old Bailey

They were privileged people who gained admission to the Old Bailey,

people with tickets from sheriffs, reporters, great actors, and very

successful authors. The early editions of the evening newspapers

announced the arrival of these latter spectators. The crowd outside the

court contented themselves with discussing the past and the probable

future of the prisoner.

The Megaphone had scored heavily again, for it published

in extenso the particulars of the prisoner’s will. It referred

to this in its editorial columns variously as ‘An Astounding Document’

and ‘An Extraordinary Fragment’. It was remarkable alike for the amount

bequeathed, and for the generosity of its legacies.

Nearly half a million was the sum disposed of, and of this the

astonishing sum of �60,000 was bequeathed to ‘the sect known as the

“Rational Faithers” for the furtherance of their campaign against

capital punishment’, a staggering legacy remembering that the Four Just

Men knew only one punishment for the people who came under its ban.

‘You want this kept quiet, of course,’ said the lawyer when the will

had been attested.

‘Not a bit,’ said Manfred; ‘in fact I think you had better hand a

copy to the Megaphone.’

‘Are you serious?’ asked the dumbfounded lawyer.

‘Perfectly so,’ said the other. ‘Who knows,’ he smiled, ‘it might

influence public opinion in—er—my favour.’

So the famous will became public property, and when Manfred,

climbing the narrow wooden stairs that led to the dock of the Old

Bailey, came before the crowded court, it was this latest freak of his

that the humming court discussed.

‘Silence!’

He looked round the big dock curiously, and when a warder pointed

out the seat, he nodded, and sat down. He got up when the indictment

was read.

‘Are you guilty or not guilty?’ he was asked, and replied

briefly:

‘I enter no plea.’

He was interested in the procedure. The scarlet-robed judge with his

old, wise face and his quaint, detached air interested him mostly. The

businesslike sheriffs in furs, the clergyman who sat with crossed legs,

the triple row of wigged barristers, the slaving bench of reporters

with their fierce whispers of instructions as they passed their copy to

the waiting boys, and the strong force of police that held the court:

they had all a special interest for him.

The leader for the Crown was a little man with a keen, strong face

and a convincing dramatic delivery. He seemed to be possessed all the

time with a desire to deal fairly with the issues, fairly to the Crown

and fairly to the prisoner. He was not prepared, he said, to labour

certain points which had been brought forward at the police-court

inquiry, or to urge the jury that the accused man was wholly without

redeeming qualities.

He would not even say that the man who had been killed, and with

whose killing Manfred was charged, was a worthy or a desirable citizen

of the country. Witnesses who had come forward to attest their

knowledge of the deceased, were ominously silent on the point of his

moral character. He was quite prepared to accept the statement he was a

bad man, an evil influence on his associates, a corrupting influence on

the young women whom he employed, a breaker of laws, a blackguard, a

debauchee.

‘But, gentlemen of the jury,’ said the counsel impressively, ‘a

civilized community such as ours has accepted a system—intricate and

imperfect though it may be—by which the wicked and the evil-minded are

punished. Generation upon generation of wise law-givers have moulded

and amended a scale of punishment to meet every known delinquency. It

has established its system laboriously, making great national

sacrifices for the principles that system involved. It has wrested with

its life-blood the charters of a great liberty—the liberty of a law

administered by its chosen officers and applied in the spirit of

untainted equity.’

So he went on to speak of the Four Just Men who had founded a

machinery for punishment, who had gone outside and had overridden the

law; who had condemned and executed their judgment independent and in

defiance of the established code.

‘Again I say, that I will not commit myself to the statement that

they punished unreasonably: that with the evidence against their

victims, such as they possessed, the law officers of the Crown would

have hesitated at initiating a prosecution. If it had pleased them to

have taken an abstract view of this or that offence, and they had said

this or that man is deserving of punishment, we, the representatives of

the established law, could not have questioned for

Comments (0)