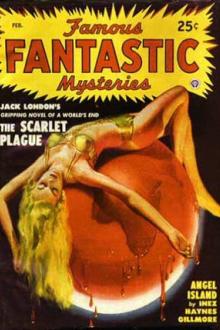

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

by one. You never heard - it was like little birds answering the

mother-bird’s call. At first their voices were faint and weak. But she

kept encouraging them until they sat up - God, it was - .”

Ralph could not go on for a while.

“She gave them a long talk - she was so weak she had to keep stopping -

but she went right on - and they listened. Of course I couldn’t

understand a word. But I knew what she said. In effect, it was: ‘We

cannot die. We must all live. We cannot leave any one of us here alone.

Promise me that you will get well!’ She pledged them to it. She made

them take an oath, one after the other. Oh, they were obedient enough.

They took it.”

He stopped again.

“That talk made the greatest difference. After it was all over, I gave

them some water. They were different even then. They looked at me - and

they didn’t shrink or shudder. When I handed Julia the cup, she made

herself smile. God, you never saw such a smile. I nearly - ” he paused,

“I all but went back to the cabin and cut my throat. But the fight’s

over. They’ll get well. They’re sleeping like children now.”

“Thank God!” Merrill groaned. “Oh, thank God!”

“I’ve felt like a murderer ever since - - ” Billy said. He stopped and

his voice leaped with a sudden querulousness. “You didn’t wake me up;

you’ve done double guard duty during the night, Ralph.”

“Oh, that’s all right. You were all in - I felt that - ” Ralph stammered

in a shamefaced fashion. “And I knew I could stand it.”

“There’s a long sleep coming to you, Ralph,” Pete said. “You’ve hardly

closed your eyes this week. No question but you’ve saved their lives.”

B.

Mid-morning on Angel Island.

The sun had mounted half-way to the zenith; sky and sea and land

glittered with its luster. Like war-horses, the waves came ramping over

the smooth, shimmering sand; war-horses with bodies of jade and manes of

silver.

Pete floated inshore on a huge comber, ran up the beach a little way and

sat down. Billy followed.

“I’ve come out just to get the picture,” Pete explained.

“Same here,” said Billy.

For an instant, both men contemplated the scene with the narrowed,

critical gaze of the artist.

The flying-girls were swimming; and swimming with the same grace and

strength with which formerly they flew. And as if inevitably they must

take on the quality of the element in which they mixed, they looked like

mermaids now, just as formerly they had looked like birds. They carried

heads and shoulders high out of the water. Webs of sea-spume glittered

on the shining hair and on the white flesh. One behind the other, they

swam in rhythmic unison. Regularly the long, round, strong-looking right

arms reached out of the water, bowed forward, clutched at the wave, and

pulled them on. Simultaneously, the left arms reached back, pushed

against the wave, and shot them forward. Their feet beat the water to a

lather.

They were headed down the beach, hugging the shore. Swim as hard as they

could, Honey and Frank managed but to keep up with them. Ralph overtook

them only in their brief resting-periods. Further inshore, carried

ceaselessly a little forward and then a little back, Julia floated;

floated with an unimaginable lightness and yet, somehow, conserved her

aspect of a creature cut in marble.

“I have never seen anything so beautiful in any art, ancient or modern,”

Billy concluded. “When those strange draperies that they affect get wet,

they look like the Elgin marbles.”

“If we should take them to civilization,” was Pete’s answer, “the Elgin

marbles would become a joke.”

Billy spoke after a long silence. “It’s been an experience that - if I

were - oh, but what’s the use? You can’t describe it. The words haven’t

been invented yet. I don’t mean the fact that we’ve discovered members

of a lost species - the missing link between bird and man. I mean what’s

happened since the capture. It’s left marks on me. I’ll bear them until

I die. If we abandoned this island - and them - and went back to the

world, I could never be the same person. If I woke up and found it was a

dream, I could never be the same person.”

“I know,” Pete said, “I know. I’ve changed, too. We all have. Old Frank

is a god. And Honey’s grown so that - . Even Ralph’s a different man.

Changed - God, I should say I had. It’s not only given me a new hold on

things I thought I’d lost-morality, ethics, religion even - but it’s

developed something I have no word for - the fourth dimension of

religion, faith.”

“It’s their weakness, I think, and their dependence.” Now it was less

that Billy tried to translate Pete’s thought and more that he endeavored

to follow his own. “It puts it up to a man so. And their beauty and

purity and innocence and simplicity - .” Billy seemed to be ransacking

his vocabulary for abstract nouns.

“And that sense you have,” Pete broke in eagerly, “of molding a virgin

mind. It gives you a feeling of responsibility that’s fairly terrifying

at times. But there’s something else mixed up with it - the instinct of

the artist. It’s as though you were trying to paint a picture on human

flesh. You know that you’re going to produce beauty.” Pete’s face shone

with the look of creative genius. “The production of beauty excuses any

method, to my way of thinking.” He spoke half to himself. “God knows,”

he added after a pause, “whatever I’ve done and been, I could never do

or be again. Sometimes a man knows when he’s reached the zenith of his

spiritual development. I’ve reached mine. I think they’re beginning to

trust us,” he added after another long interval, in which silently they

contemplated the moving composition. Pete’s tone had come back to its

everyday accent.

“No question about it,” Billy rejoined. “If I do say it as shouldn’t, I

think my scheme was the right one - never to separate any one of them

from the others, never to seem to try to get them alone, and in

everything to be as gentle and kind and considerate as we could.”

“That look is still in their eyes,” Pete said. He turned away from Billy

and his face contracted. “It goes through me like a knife - - . When

that’s gone - - .”

“It will go inevitably, Pete,” Billy reassured him cheerfully. Suddenly

his own voice lowered. “One queer thing I’ve noticed. I wonder if you’re

affected that way. I always feel as if they still had wings. What I mean

is this. If I stand beside one of them with my eyes turned away I always

get an impression that they’re still there, towering above my head -

ghosts of wings. Ever notice it?”

“Oh, Lord, yes!” Pete agreed. “Often. I hate it. But that will go, too.

Here they come.”

The bathers had turned; they were swimming up the beach. They passed

Julia, who joined the procession, and turned toward the land. Stretched

in a long line, they rode in on a big wave. Billy and Pete leaped

forward. Assisted by the men, the girls tottered up the sand, gathered

into a little group, talking among themselves. Their wet draperies clung

to them in long, sweeping lines; but they dried with amazing quickness.

The sun grew hotter and hotter. Their transient flash of animation died

down; their conversation gradually stopped.

Chiquita settled herself flat on the sand, the sunlight pouring like a

silver liquid into the blue-black masses of her hair, her narrow brows,

her thick eyelashes. Presently she fell asleep. Clara leaned against a

low ledge of rock and spread her coppery mane across its surface. It

dried almost immediately; she divided it into plaits and coils and wove

it into an elaborate structure. Her fingers seemed to strike sparks from

it; it coruscated. Julia lay on her side, eyes downcast, tracing with

one finger curious tangled patterns in the sand. Her hair blew out and

covered her body as with a silken, honey-colored fabric; the lines of

her figure were lost in its abundance. Peachy sat drooped over, her hand

supporting her chin and her knees supporting her elbows, her eyes fixed

on the horizon-line. Her hair dried, too, but she did not touch it. It

flowed down her back and spread into a pool of gold on the sand. She

might have been a mermaid cast up by that sea on which she gazed with

such a tragic wistfulness - and forever cut off from it.

A little distance from the rest, Honey sat with Lulu. She was shaking

the brown masses of her hair vigorously and Honey was helping her. He

was evidently trying to teach her something because, over and over

again, his lips moved to form two words, and over and over again, her

red lips parted, mimicking them. Gradually, Lulu lost all interest in

her hair. She let it drop. It floated like a furry mantle over her

shoulders. Into her little brown, pointed face came a look of

overpowering seriousness, of tremendous concentration. Occasionally

Honey would stop to listen to her; but invariably her recital sent him

into peals of laughter. Lulu did not laugh; she grew more and more

serious, more and more concentrated.

The other men talked among themselves. Occasionally they addressed a

remark to their captives. The flying-girls replied in hesitating

flutters of speech, a little breathy yes or no whenever those

monosyllables would serve, an occasional broken phrase. Superficially

they seemed calm, placid even. But if one of the men moved suddenly, an

uncontrollable panic overspread their faces.

Honey arose after a long interval, strolled over to the main group.

“I think they’re coming to the conclusion that we’re regular fellows,”

he declared cheerfully. “Lulu doesn’t jump or shriek any more when I run

toward her.”

“Oh, it’s coming along all right,” Frank said.

“It’s surprising how quickly and how correctly they’re getting the

language.”

“I’m going to begin reading aloud to them next week,” Pete announced.

“That’ll be a picnic.”

“It’s been a long fight,” Ralph said contentedly. “But we’ve won out.

We’ve got them going. I knew we would.” His eyes went to Peachy’s face,

but once there, their look of triumph melted to tenderness.

“What are we going to read them?” Honey asked idly. He did not really

listen to Pete’s answer. His eyes, sparkling with amusement, had gone

back to Lulu, who still sat seriously practising her lesson. Red lips,

little white teeth, slender pink tongue seemed to get into an

inextricable tangle over the simple monosyllables.

“Leave that to me!” Pete was saying mysteriously. “I’ll have them

reading and writing by the end of another two months.”

“It’s curious how long it’s taken them to get over that terror of us,”

said Billy. “I cannot understand it.”

“Oh, they’ll explain why they’ve been so afraid,” said Frank, “as soon

as they’ve got enough vocabulary. We cannot know, until they tell us how

many of their conventions we have broken, how brutal we may have

seemed.”

“And yet,” Billy went on, “I should think they’d see that we wouldn’t do

anything that wasn’t for their own good. Well, just as soon as I can put

it over with them, I’m going to give them a long spiel on the

gentleman’s code. I don’t

Comments (0)