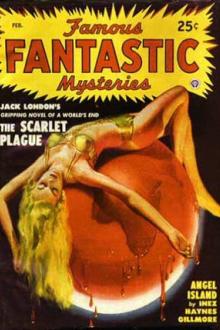

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

sleeping face. She turned the baby over. She pulled the single light

garment off. Then she looked up at the other women.

The little naked figure lay in the golden sunlight, translucent, like an

angel carved in alabaster. But on the shoulder-blades lay shadow, deep

shadow - no, not shadow, a fluff of feathery down.

“Wings!” Peachy said. “My little girl is going to fly!”

“Wings!” the others repeated. “Wings!”

And then the room seemed to fill with tears that ended in laughter, and

laughter that ended in tears.

VIThey won’t be home until very late tonight,” announced Lulu. “The work

they’re doing now is hard and irritating and fussy. Honey says that they

want to get through with it as soon as possible. He said they’d keep at

it as long as the light lasted.”

“It seems as if their working days grew longer all the time,” Clara said

petulantly. “They start off earlier and earlier in the morning and they

stay later and later at night. And did you know that they are planning

soon to stay a week at the New Camp - they say the walk back is so

fatiguing after a long day’s work.”

The others nodded.

“And then the instant they’ve had their dinner,” Lulu continued, “off

they go to that tiresome Clubhouse - for tennis and ball and bocci. It

seems, somehow, as if I never had a chance to talk with Honey nowadays.

I should think they’d get enough of each other, working side by side all

day long, the way they do. But no! The moment they’ve eaten and had

their smoke, they must get together again. Why is it, I wonder? I should

think they would have said all they had to say in the daytime.”

“Pete is worse than any of them,” Clara went on. “After he comes back

from the Clubhouse, he wants to sit up and write for an hour or two. Oh,

I get fairly desperate sometimes, sitting there listening to the eternal

scratching of his pen. I cannot understand his point of view, to save my

life. If I talk, it irritates him. My very breathing annoys him; he

cannot have me in the same room with him. But if I leave the cabin, he

can’t write a word. He wants me near, always. He says it’s the knowing

I’m there that makes him feel like writing. And then Sundays, if he

isn’t writing, he’s painting. I don’t mind his not being there in the

daytime in a way because, of course, there’s always Peterkin. But at

night, when I’ve put Peterkin to bed I do want something different to

happen. As it is, I have to make a scene to get up any excitement. I do

it, too, without compunction. When it gets to the point that I know I

must scream or go crazy, I scream. And I do a good job in screaming,

too.”

“What would you like him to do, Clara?” Julia asked.

The petulant frown between Clara’s eyebrows deepened. “I don’t know,”

she said wearily. “I don’t know what it is that I want to do; but I want

to do something. Peterkin is asleep and perfectly safe - and I feel like

going somewhere. Now, if I could fly, it would rest me so, to go for a

long, long journey through the air.” As she concluded, some new

expression, some strange hardness of her maturity, melted; her face was

for an instant the face of the old Clara.

Julia made no comment.

It was Chiquita who took it up.

“My husband talks enough. In fact, he talks all the time. But if I tire

of his voice, I let myself fall asleep. He never notices. That is why

I’ve grown so big. Sometimes ” - discontent dulled for an instant the

slow fire of her slumberous eyes - ” sometimes my life seems one long

sleep. If it weren’t for junior, I’d feel as if I weren’t quite alive.”

“Ralph talks a great deal,” Peachy said listlessly, “by fits and starts,

and he takes me out when he comes home, if he happens to feel like

walking himself. He says, though, that it exhausts him having to help me

along. But it isn’t that I want particularly. Often I want to go out

alone. I want to soar. The earth has never satisfied me. I want to

explore the heights. I want to explore them alone, and I want to explore

them when the mood seizes me. And I want to feel when I come back that I

can talk about it or keep silent as he does. But I must make my

discoveries and explorations in my own way. Ralph sometimes gives me

long talks about astronomy - he seems to think that studying about the

stars will quiet me. One little flight straight up would mean more to me

than all that talk. Ralph does not understand it in me, and I cannot

explain it to him. And yet he feels exactly that way himself - he’s

always going off by himself through unexplored trails on the island. But

he cannot comprehend how I, being a woman, should have the same desire.

Do you remember when our wings first began to grow strong and our people

kept us confined, how we beat our wings against the wall - beat and beat

and beat? At times now, I feel exactly like that. Why, sometimes I envy

little Angela her wings.”

The five women reclined on long, low rustic couches in the big, cleared

half-oval that was the Playground for their children. It began - this

half-oval - in high land among the trees and spread down over a beach to

the waters of a tiny cove. Between the high tapering boles of the pines

at their back the sky dropped a curtain of purple. Between the long

ledges of tawny rock in front the sea stretched a carpet of turquoise.

And between pines and sea lay first a rusty mat of pine-needles, then a,

ribbon of purple stones, then a band of glittering sand. In the air the

resinous smell of the pines competed with the salty tang of the ocean.

High up, silver-winged gulls curved and dipped and called their creaking

signals.

At the water’s edge four children were playing. Honey-Boy had waded out

waist-deep. A sturdy, dark, strong-bodied, tiny replica of his father,

he stood in an exact reproduction of one of Honey’s poses, his arms

folded over his little pouter-pigeon chest, lips pursed, brows frowning,

dimples inhibited, gazing into the water. Just beyond, one foot on the

bottom, Peterkin pretended to swim. Peterkin had an unearthly beauty

that was half Clara’s coloring - combination of tawny hair with

gray-green eyes - and half Pete’s expression - the look, doubly strange,

of the Celt and the genius. Slender and beautifully formed, graceful, he

was in every possible way a contrast to virile little Billy-Boy; he was

even elegant; he had the look of a story-book prince. Far up the beach,

cuddled in a warm puddle, naked, sat a fat, redheaded baby, Frank

Merrill, junior. He watched the others intently for a while. Then

breaking into a grin which nearly bisected the face under the fiery

thatch, he began an imitative paddle with his pudgy hands and feet.

Flitting hither and yon, hovering one moment at the water’s edge and

another at Junior’s side, moving with a capricious will-o’-the-wisp

motion that dominated the whole picture, flew Angela.

Beautiful as the other children were, they sank to commonplaces in

contrast with Angela.

For Angela was a being of faery. Her single loose garment, serrated at

the edges, knee-length, and armless, left slits at the back for a pair

of wings to emerge. Tiny these wings were, and yet they were perfect in

form; they soared above her head, soft, fine, shining, delicate as

milkweed-down and of a white that was beginning, near the shoulders, to

deepen to a pale rose. Angela’s little body was as slender as a

flower-stem. Her limbs showed but the faintest of curves, her skin but

the faintest of tints. Almost transparent in the sunlight, she had in

the shadow the coloring of the opal, pale rose-pinks and pale

violet-blues. Her hair floated free to her shoulders; and that, more

than any other detail, seemed to accent the quality of faery in her

personality. In calm it clung to her head like a pale-gold mist; in

breeze it floated away like a pale-gold nimbus. It seemed as though a

shake of her head would send it drifting off - a huge thistle-down of

gold. Her eyes reflected the tint of whatever blue they gazed on,

whether it was the frank azure of the sky or the mysterious turquoise of

the sea. And yet their look was strangely intent. When she passed from

shadow to sunshine, the light seemed to dissolve her hair and

wing-edges, as though it were gradually taking her to itself.

“Oh, yes, Peachy,” Lulu said, “Angela’s wings must be a comfort to you.

You must live it all over again in her.”

“I do!” answered Peachy. “I do.” There was tremendous conviction in her

voice, as though she were defending herself from some silent accusation.

“But it isn’t the same. It isn’t. It can’t be. Besides, I want to fly

with her.”

The ripples in the cove grew to little waves, to big waves, to combers.

The women talked and the children played. Honey-Boy and Peterkin waded

out to their shoulders, dipped, and pretended to swim back. Angela flew

out to meet a wave bigger than the others, balanced on its crest. Wings

outspread, she fluttered back, descended when the crash came in a shower

of rainbow drops. She dipped and rose, her feathers dripping molten

silver, flew on to the advancing crest.

“Oh,” Lulu sighed, “I do want a little girl. I threatened if this one

was a boy to drown it.” “This one” proved to be a bundle lying on the

pine-needles at her side. The bundle stirred and emitted a querulous

protest. She picked it up and it proved to be a baby, just such another

sturdy little dark creature as Honey-Boy must have been. “Your mother

wouldn’t exchange you for a million girls now,” Lulu addressed him

fondly. “I pray every night, though, that the next one will be a girl.”

“I want a girl, too,” Clara remarked. “Well, we’ll see next spring.”

Clara had not been happy at the prospect of her first maternity, but she

was jubilant over her second.

“It will be nice for Angela, too,” Peachy said, to have some little girl

to play with. Come, baby!” she called in a sudden access of tenderness.

Angela flew down from the tip of a billow, came fluttering and flying up

the beach. Once or twice, for no apparent reason, her wings fell dead,

sagged for a few moments; then her little pink, shell-like feet would

pad helplessly on the sand. Twice she dropped her pinions deliberately;

once to climb over a big root, once to mount a boulder that lay in her

path. “Don’t walk, Angela!” Peachy called sharply at these times. “Fly!

Fly!” And obediently, Angela stopped, waited until the strength flowed

into her wings, started again. She reached the group of mothers, not by

direct flight, but a complicated method of curving, arching, dipping,

and circling. Peachy arose, balanced herself, caught her little daughter

in midair, kissed her. The women handed her from one to the other,

petting and caressing her.

Julia received her last. She sat with Angela in the curve of her arm,

one hand caressing the drooped wings.

Comments (0)