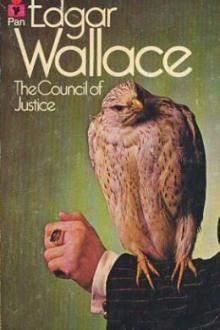

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

justice of their reasoning. But we have come into conflict on the

question of the adequacy of punishment, and upon the more serious

question of the right of the individual to inflict that punishment,

which results in the appearance of this man in the dock on a charge of

murder.’

Throughout the opening speech, Manfred leant forward, following the

counsel’s words.

Once or twice he nodded, as though he were in agreement with the

speaker, and never once did he show sign of dissent.

The witnesses came in procession. The constable again, and the

doctor, and the voluble man with the squint. As he finished with each,

the counsel asked whether he had any question to put, but Manfred shook

his head.

‘Have you ever seen the accused before?’ the judge asked the last

witness.

‘No, sar, I haf not,’ said the witness emphatically, ‘I haf not’ing

to say against him.’

As he left the witness-box, he said audibly:

‘There are anoder three yet—I haf no desire to die,’ and amidst the

laughter that followed this exhibition of caution, Manfred recalled him

sharply.

‘If you have no objection, my lord?’ he said.

‘None whatever,’ replied the judge courteously.

‘You have mentioned something about another three,’ he said. ‘Do you

suggest that they have threatened you?’

‘No, sar—no!’ said the eager little man.

‘I cannot examine counsel,’ said Manfred, smiling; ‘but I put it to

him, that there has been no suggestion of intimidation of witnesses in

this case.’

‘None whatever,’ counsel hastened to say; ‘it is due to you to make

that statement.’

‘Against this man’—the prisoner pointed to the witness-box—‘we

have nothing that would justify our action. He is a saccharine

smuggler, and a dealer in stolen property—but the law will take care

of him.’

‘It’s a lie,’ said the little man in the box, white and shaking; ‘it

is libellous!’

Manfred smiled again and dismissed him with a wave of his hand.

The judge might have reproved the prisoner for his irrelevant

accusation, but allowed the incident to pass.

The case for the prosecution was drawing to a close when an official

of the court came to the judge’s side and, bending down, began a

whispered conversation with him.

As the final witness withdrew, the judge announced an adjournment

and the prosecuting counsel was summoned to his lordship’s private

room.

In the cells beneath the court, Manfred received a hint at what was

coming and looked grave.

After the interval, the judge, on taking his seat, addressed the

jury:

‘In a case presenting the unusual features that characterize this,’

he said, ‘it is to be expected that there will occur incidents of an

almost unprecedented nature. The circumstances under which evidence

will be given now, are, however, not entirely without precedent.’ He

opened a thick law book before him at a place marked by a slip of

paper. ‘Here in the Queen against Forsythe, and earlier, the Queen

against Berander, and earlier still and quoted in all these rulings,

the King against Sir Thomas Mandory, we have parallel cases.’ He closed

the book.

‘Although the accused has given no intimation of his desire to call

witnesses on his behalf, a gentleman has volunteered his evidence. He

desires that his name shall be withheld, and there are peculiar

circumstances that compel me to grant his request. You may be assured,

gentlemen of the jury, that I am satisfied both as to the identity of

the witness, and that he is in every way worthy of credence.’

He nodded a signal to an officer, and through the judge’s door to

the witness box there walked a young man. He was dressed in a tightly

fitting frock coat, and across the upper part of his face was a half

mask.

He leant lightly over the rail, looking at Manfred with a little

smile on his clean-cut mouth, and Manfred’s eyes challenged him.

‘You come to speak on behalf of the accused?’ asked the judge.

‘Yes, my lord.’

It was the next question that sent a gasp of surprise through the

crowded court.

‘You claim equal responsibility for his actions?’

‘Yes, my lord!’

‘You are, in fact, a member of the organization known as the Four

Just Men?’

‘I am.’

He spoke calmly, and the thrill that the confession produced, left

him unmoved.

‘You claim, too,’ said the judge, consulting a paper before him, ‘to

have participated in their councils?’

‘I claim that.’

There were long pauses between the questions, for the judge was

checking the replies and counsel was writing busily.

‘And you say you are in accord both with their objects and their

methods?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘You have helped carry out their judgment?’

‘I have.’

‘And have given it the seal of your approval?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you state that their judgments were animated with a high sense

of their duty and responsibility to mankind?’

‘Those were my words.’

‘And that the men they killed were worthy of death?’

‘Of that I am satisfied.’

‘You state this as a result of your personal knowledge and

investigation?’

‘I state this from personal knowledge in two instances, and from the

investigations of myself and the independent testimony of high legal

authority.’

‘Which brings me to my next question,’ said the judge. ‘Did you ever

appoint a commission to investigate all the circumstances of the known

cases in which the Four Just Men have been implicated?’

‘I did.’

‘Was it composed of a Chief Justice of a certain European State, and

four eminent criminal lawyers?’

‘It was.’

‘And what you have said is the substance of the finding of that

Commission?’

‘Yes.’

The Judge nodded gravely and the public prosecutor rose to

cross-examination.

‘Before I ask you any question,’ he said, ‘I can only express myself

as being in complete agreement with his lordship on the policy of

allowing your identity to remain hidden.’ The young man bowed.

‘Now,’ said the counsel, ‘let me ask you this. How long have you

been in association with the Four Just Men?’

‘Six months,’ said the other.

‘So that really you are not in a position to give evidence regarding

the merits of this case—which is five years old, remember.’

‘Save from the evidence of the Commission.’

‘Let me ask you this—but I must tell you that you need not answer

unless you wish—are you satisfied that the Four Just Men were

responsible for that tragedy?’

‘I do not doubt it,’ said the young man instantly. ‘Would anything

make you doubt it?’

‘Yes,’ said the witness smiling, ‘if Manfred denied it, I should not

only doubt it, but be firmly assured of his innocence.’

‘You say you approve both of their methods and their objects?’

‘Yes.’

‘Let us suppose you were the head of a great business firm

controlling a thousand workmen, with rules and regulations for their

guidance and a scale of fines and punishments for the preservation of

discipline. And suppose you found one of those workmen had set himself

up as an arbiter of conduct, and had superimposed upon your rules a

code of his own.’

‘Well?’

‘Well, what would be your attitude toward that man?’

‘If the rules he initiated were wise and needful I would incorporate

them in my code.’

‘Let me put another case. Suppose you governed a territory,

administering the laws—’

‘I know what you are going to say,’ interrupted the witness, ‘and my

answer is that the laws of a country are as so many closely-set palings

erected for the benefit of the community. Yet try as you will, the

interstices exist, and some men will go and come at their pleasure,

squeezing through this fissure, or walking boldly through that

gap.’

‘And you would welcome an unofficial form of justice that acted as a

kind of moral stop-gap?’

‘I would welcome clean justice.’

‘If it were put to you as an abstract proposition, would you accept

it?’

The young man paused before he replied.

‘It is difficult to accommodate one’s mind to the abstract, with

such tangible evidence of the efficacy of the Four Just Men’s system

before one’s eyes,’ he said.

‘Perhaps it is,’ said the counsel, and signified that he had

finished.

The witness hesitated before leaving the box, looking at the

prisoner, but Manfred shook his head smilingly, and the straight slim

figure of the young man passed out of court by the way he had come.

The unrestrained buzz of conversation that followed his departure

was allowed to go unchecked as judge and counsel consulted earnestly

across the bench.

Garrett, down amongst the journalists, put into words the vague

thought that had been present in every mind in court.

‘Do you notice, Jimmy,’ he said to James Sinclair of the

Review, ‘how blessed unreal this trial is? Don’t you miss the

very essence of a murder trial, the mournfulness of it and the horror

of it? Here’s a feller been killed and not once has the prosecution

talked about “this poor man struck down in the prime of

life” or said anything that made you look at the prisoner to see

how he takes it. It’s a philosophical discussion with a hanging at the

end of it.’

‘Sure,’ said Jimmy.

‘Because,’ said Garrett, ‘if they find him guilty, he’s got to die.

There’s no doubt about that; if they don’t hang him, crack! goes the

British Constitution, the Magna Charta, the Diet of Worms, and a few

other things that Bill Seddon was gassing about.’

His irreverent reference was to the prosecutor’s opening speech. Now

Sir William Seddon was on his feet again, beginning his closing address

to the jury. He applied himself to the evidence that had been given, to

the prisoner’s refusal to call that evidence into question, and

conventionally traced step by step the points that told against the man

in the dock. He touched on the appearance of the masked figure in the

witness-box. For what it was worth it deserved their consideration, but

it did not affect the issue before the court. The jury were there to

formulate a verdict in accordance with the law as it existed, not as if

it did not exist at all, to apply the law, not to create it—that was

their duty. The prisoner would be offered an opportunity to speak in

his own defence. Counsel for the Crown had waived his right to make the

final address. They would, if he spoke, listen attentively to the

prisoner, giving him the benefit of any doubt that might be present in

their minds. But he could not see, he could not conceivably imagine,

how the jury could return any but one verdict.

It seemed for a while that Manfred did not intend availing himself

of the opportunity, for he made no sign, then he rose to his feet, and,

resting his hands on the inkstand ledge before him:

‘My lord,’ he said, and turned apologetically to the jury, ‘and

gentlemen.’

The court was so still that he could hear the scratchings of the

reporters’ pens, and unexpected noises came from the street

outside.

‘I doubt either the wisdom or the value of speaking,’ he said, ‘not

that I suggest that you have settled in your minds the question of my

guilt without very excellent and convincing reasons.

‘I am under an obligation to Counsel for the Treasury,’ he bowed to

the watchful prosecutor, ‘because he spared me those banalities of

speech which I

Comments (0)