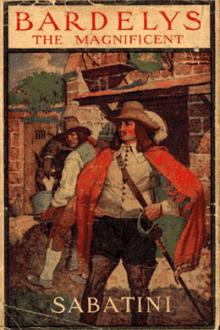

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

before God that you shall not go unpunished.”

“I think, monsieur, that you run a grave risk of perjuring yourself!”

I laughed.

“You shall render me satisfaction ere we part!” he cried.

“If you do not deem that paper satisfaction enough, then, monsieur,

forgive me, but your greed transcends all possibility of being ever

satisfied.”

“The devil take your paper and your estates! What shall they

profit me when I am dead?”

“They may profit your heirs,” I suggested.

“How shall that profit me?”

“That is a riddle that I cannot pretend to elucidate.”

“You laugh, you knave!” he snorted. Then, with an abrupt change of

manner, “You do not lack for friends,” said he. “Beg one of these

gentlemen to act for you, and if you are a man of honour let us step

out into the yard and settle the matter.”

I shook my head.

“I am so much a man of honour as to be careful with whom I cross

steel. I prefer to leave you to His Majesty’s vengeance; his

headsman may be less particular than am I. No, monsieur, on the

whole, I do not think that I can fight you.”

His face grew a shade paler. It became grey; the jaw was set, and

the eyes were more out of symmetry than I had ever seen them. Their

glance approached what is known in Italy as the mal’occhio, and to

protect themselves against the baneful influences of which men carry

charms. A moment he stood so, eyeing me. Then, coming a step

nearer—

“You do not think that you can fight me, eh? You do not think it?

Pardieu! How shall I make you change your mind? To the insult of

words you appear impervious. You imagine your courage above dispute

because by a lucky accident you killed La Vertoile some years ago

and the fame of it has attached to you.” In the intensity of his

anger he was breathing heavily, like a man overburdened. “You have

been living ever since by the reputation which that accident gave

you. Let us see if you can die by it, Monsieur de Bardelys.” And,

leaning forward, he struck me on the breast, so suddenly and so

powerfully - for he was a man of abnormal strength - that I must

have fallen but that La Fosse caught me in his arms.

“Kill him!” lisped the classic-minded fool. “Play Theseus to this

bull of Marathon.”

Chatellerault stood back, his hands on his hips, his head inclined

towards his right shoulder, and an insolent leer of expectancy upon

his face.

“Will that resolve you?” he sneered.

“I will meet you,” I answered, when I had recovered breath. “But I

swear that I shall not help you to escape the headsman.”

He laughed harshly.

“Do I not know it?” he mocked. “How shall killing you help me to

escape? Come, messieurs, sortons. At once!”

“Sor,” I answered shortly; and thereupon we crowded from the room,

and went pele-mele down the passage to the courtyard at the back.

SWORDS!

La Fosse led the way with me, his arm through mine, swearing that

he would be my second. He had such a stomach for a fight, had this

irresponsible, irrepressible rhymester, that it mounted to the

heights of passion with him, and when I mentioned, in answer to a

hint dropped in connection with the edict, that I had the King’s

sanction for this combat, he was nearly mad with joy.

“Blood of La Fosse!” was his oath. “The honour to stand by you

shall be mine, my Bardelys! You owe it me, for am I not in part to

blame for all this ado? Nay, you’ll not deny me. That gentleman

yonder, with the wild-cat moustaches and a name like a Gascon oath

—that cousin of Mironsac’s, I mean - has the flair of a fight in

his nostrils, and a craving to be in it. But you’ll grant me the

honour, will you not? Pardieu! It will earn me a place in history.”

“Or the graveyard,” quoth I, by way of cooling his ardour.

“Peste! What an augury!” Then, with a laugh: “But,” he added,

indicating Saint-Eustache, “that long, lean saint - I forget of what

he is patron - hardly wears a murderous air.”

To win peace from him, I promised that he should stand by me. But

the favour lost much of its value in his eyes when presently I added

that I did not wish the seconds to engage, since the matter was of

so very personal a character.

Mironsac and Castelroux, assisted by Saint-Eustache, closed the

heavy portecochere, and so shut us in from the observation of

passers-by. The clanging of those gates brought the landlord and a

couple of his knaves, and we were subjected to the prayers and

intercessions, to the stormings and ravings that are ever the prelude

of a stable-yard fight, but which invariably end, as these ended, in

the landlord’s withdrawal to run for help to the nearest

corps-de-garde.

“Now, my myrmillones,” cried La Fosse in bloodthirsty jubilation, “to

work before the host returns.”

“Po’ Cap de Dieu!” growled Castelroux, “is this a time for jests,

master joker?”

“Jests?” I heard him retorting, as he assisted me to doff my doublet.

“Do I jest? Diable! you Gascons are a slow-witted folk! I have a

taste for allegory, my friend, but that never yet was accounted so

low a thing as jesting.”

At last we were ready, and I shifted the whole of my attention to

the short, powerful figure of Chatellerault as he advanced upon me,

stripped to the waist, his face set and his eyes full of stern

resolve. Despite his low stature, and the breadth of frame which

argue sluggish motion, there was something very formidable about the

Count. His bared arms were great masses of muscular flesh, and if

his wrist were but half as supple as it looked powerful, that alone

should render him a dangerous antagonist.

Yet I had no qualm of fear, no doubt, even, touching the issue. Not

that I was an habitual ferrailleur. As I have indicated, I had

fought but one man in all my life. Nor yet am I of those who are

said to know no fear under any circumstances. Such men are not

truly brave; they are stupid and unimaginative, in proof of which I

will advance the fact that you may incite a timid man to deeds of

reckless valour by drugging him with wine. But this is by the way.

It may be that the very regular fencing practice that in Paris I was

wont to take may so have ordered my mind that the fact of meeting

unbaited steel had little power to move me.

Be that as it may, I engaged the Count without a tremor either of

the flesh or of the spirit. I was resolved to wait and let him open

the play, that I might have an opportunity of measuring his power

and seeing how best I might dispose of him. I was determined to do

him no hurt, and to leave him, as I had sworn, to the headsman; and

so, either by pressure or by seizure, it was my aim to disarm him.

But on his side also he entered upon the duel with all caution and

wariness. From his rage I had hoped for a wild, angry rush that

should afford me an easy opportunity of gaining my ends with him.

Not so, however. Now that he came with steel to defend his life and

to seek mine, he appeared to have realized the importance of having

keen wits to guide his hand; and so he put his anger from him, and

emerged calm and determined from his whilom disorder.

Some preliminary passes we made from the first engagement in the

lines of tierce, each playing warily for an opening, yet neither of

us giving ground or betraying haste or excitement. Now his blade

slithered on mine with a ceaseless tremor; his eyes watched mine

from under lowering brows, and with knees bent he crouched like a

cat making ready for a spring. Then it came. Sudden as lightning

was his disengage; he darted under my guard, then over it, then

back and under it again, and stretching out in the lunge - his

double-feint completed - he straightened his arm to drive home the

botte.

But with a flying point I cleared his blade out of the line of my

body. There had been two sharp tinkles of our meeting swords, and

now Chatellerault stood at his fullest stretch, the half of his

steel past and behind me, for just a fraction of time completely

at my mercy. Yet I was content to stand, and never move my blade

from his until he had recovered and we were back in our first

position once again.

I heard the deep bass of Castelroux’s “Mordieux!” the sharp gasp of

fear from Saint-Eustache, who already in imagination beheld his

friend stretched lifeless on the ground, and the cry of mortification

from La Fosse as the Count recovered. But I heeded these things

little. As I have said, to kill the Count was not my object. It

had been wise, perhaps, in Chatellerault to have appreciated that

fact; but he did not. From the manner in which he now proceeded to

press me, I was assured that he set his having recovered guard to

slowness on my part, never thinking of the speed that had been

necessary to win myself such an opening as I had obtained.

My failure to run him through in that moment of jeopardy inspired

him with a contempt of my swordplay. This he now made plain by the

recklessness with which he fenced, in his haste to have done ere we

might chance to be interrupted. Of this recklessness I suddenly

availed myself to make an attempt at disarming him. I turned aside

a vicious thrust by a close - a dangerously close - parry, and

whilst in the act of encircling his blade I sought by pressure to

carry it out of his hand. I was within an ace of succeeding, yet

he avoided me, and doubled back.

He realized then, perhaps, that I was not quite so contemptible an

antagonist as he had been imagining, and he went back to his earlier

and more cautious tactics. Then I changed my plans. I simulated

an attack, and drove him hard for some moments. Strong he was, but

there were advantages of reach and suppleness with me, and even

these advantages apart, had I aimed at his life, I could have made

short work of him. But the game I played was fraught with perils

to myself, and once I was in deadly danger, and as near death from

the sword as a man may go and live. My attack had lured him, as I

desired that it should, into making a riposte. He did so, and as

his blade twisted round mine and came slithering at me, I again

carried it off by encircling it, and again I exerted pressure to

deprive him of it. But this time I was farther from success than

before. He laughed at the attempt, as with a suddenness that I had

been far from expecting he disengaged again, and his point darted

like a snake upwards at my throat.

I parried that thrust, but I only parried it when it was within

some three inches of my neck, and even as I turned it aside it

missed me as narrowly as it might without tearing my

Comments (0)