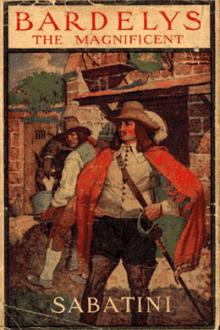

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

would seem, was well informed; he had drawn all knowledge of the

state of things from Castelroux’s messenger, and later - I know not

from whom - at Toulouse, since his arrival.

He regaled the company, therefore, with a recital of our finding

the dying Lesperon, and of how I had gone off alone, and evidently

assumed the name and role of that proscribed rebel, and thus

conducted my wooing under sympathy inspiring circumstances at

Lavedan. Then came, he announced, the very cream of the jest, when

I was arrested as Lesperon and brought to Toulouse and to trial in

Lesperon’s stead; he told them how I had been sentenced to death

in the other man’s place, and he assured them that I would certainly

have been beheaded upon the morrow but that news had been borne to

him - Rodenard - of my plight, and he was come to deliver me.

My first impulse upon hearing him tell of the wager had been to

stride into the room and silence him by my coming. That I did not

obey that impulse was something that presently I was very bitterly

to regret. How it came that I did not I scarcely know. I was

tempted, perhaps, to see how far this henchman whom for years I had

trusted was unworthy of that trust. And so, there in the porch, I

stayed until he had ended by telling the company that he was on his

way to inform the King - who by great good chance was that day

arrived in Toulouse - of the mistake that had been made, and thus

obtain my immediate enlargement and earn my undying gratitude.

Again I was on the point of entering to administer a very stern

reproof to that talkative rogue, when of a sudden there was a

commotion within. I caught a scraping of chairs, a dropping of

voices, and then suddenly I found myself confronted by Roxalanne de

Lavedan herself, issuing with a page and a woman in attendance.

For just a second her eyes rested on me, and the light coming through

the doorway at her back boldly revealed my countenance. And a very

startled countenance it must have been, for in that fraction of time

I knew that she had heard all that Rodenard had been relating. Under

that instant’s glance of her eyes I felt myself turn pale; a shiver

ran through me, and the sweat started cold upon my brow. Then her

gaze passed from me, and looked beyond into the street, as though

she had not known me; whether in her turn she paled or reddened I

cannot say, for the light was too uncertain. Next followed what

seemed to me an interminable pause, although, indeed, it can have

been no more than a matter of seconds - aye, and of but few. Then,

her gown drawn well aside, she passed me in that same irrecognizing

way, whilst I, abashed, shrank back into the shadows of the porch,

burning with shame and rage and humiliation.

From under her brows her woman glanced at me inquisitively; her

liveried page, his nose in the air, eyed me so pertly that I was

hard put to it not to hasten with my foot his descent of the steps.

At last they were gone, and from the outside the shrill voice of

her page was wafted to me. He was calling to the ostler for her

carriage. Standing, in my deep mortification, where she had passed

me, I conjectured from that demand that she was journeying to Lavedan.

She knew now how she had been cheated on every hand, first by me

and later, that very afternoon, by Chatellerault, and her resolve to

quit Toulouse could but signify that she was done with me for good.

That it had surprised her to find me at large already, I fancied I

had seen in her momentary glance, but her pride had been quick to

conquer and stifle all signs of that surprise.

I remained where she had passed me until her coach had rumbled away

into the night, and during the moments that elapsed I had stood

arguing with myself and resolving upon my course of action. But

despair was fastening upon me.

I had come to the Hotel de l’Epee, exulting, joyous, and confident

of victory. I had come to confess everything to her, and by virtue

of what I had done that confession was rendered easy. I could have

said to her: “The woman whom I wagered to win was not you, Roxalanne,

but a certain Mademoiselle de Lavedan. Your love I have won, but

that you may foster no doubts of my intentions, I have paid my wager

and acknowledge defeat. I have made over to Chatellerault and to

his heirs for all time my estates of Bardelys.”

Oh, I had rehearsed it in my mind, and I was confident - I knew -

that I should win her. And now - the disclosure of that shameful

traffic coming from other lips than mine had ruined everything by

forestalling my avowal.

Rodenard should pay for it - by God, he should! Once again did I

become a prey to the passion of anger which I have ever held to

be unworthy in a gentleman, but to which it would seem that I was

growing accustomed to give way. The ostler was mounting the steps

at the moment. He carried in his hand a stout horsewhip with a

long knotted thong. Hastily muttering a “By your leave,” I snatched

it from him and sprang into the room.

My intendant was still talking of me. The room was crowded, for

Rodenard alone had brought with him my twenty followers. One of

these looked up as I brushed past him, and uttered a cry of surprise

upon recognizing me. But Rodenard talked on, engrossed in his theme

to the exclusion of all else.

“Monsieur le Marquis,” he was saying, “is a gentleman whom it is,

indeed, an honour to serve—”

A scream burst from him with the last word, for the lash of my whip

had burnt a wheal upon his well-fed sides.

“It is an honour that shall be yours no more, you dog!” I cried.

He leapt high into the air as my whip cut him again. He swung round,

his face twisted with pain, his flabby cheeks white with fear, and

his eyes wild with anger, for as yet the full force of the situation

had not been borne in upon him. Then, seeing me there, and catching

something of the awful passion that must have been stamped upon my

face, he dropped on his knees and cried out something that I did

not understand for I was past understanding much just then.

The lash whistled through the air again and caught him about the

shoulders. He writhed and roared in his anguish of both flesh and

spirit. But I was pitiless. He had ruined my life for me with his

talking, and, as God lived, he should pay the only price that it

lay in his power to pay - the price of physical suffering. Again

and again my whip hissed about his head and cut into his soft white

flesh, whilst roaring for mercy he moved and rocked on his knees

before me. Instinctively he approached me to hamper my movements,

whilst I moved back to give my lash the better play. He held out

his arms and joined his fat hands in supplication, but the lash

caught them in its sinuous tormenting embrace, and started a red

wheal across their whiteness. He tucked them into his armpits with

a scream, and fell prone upon the ground.

Then I remember that some of my men essayed to restrain me, which

to my passion was as the wind to a blaze. I cracked my whip about

their heads, commanding them to keep their distance lest they were

minded to share his castigation. And so fearful an air must I

have worn, that, daunted, they hung back and watched their leader’s

punishment in silence.

When I think of it now, I take no little shame at the memory of how

I beat him. It is, indeed, with deep reluctance and yet deeper

shame that I have brought myself to write of it. If I offend you

with this account of that horsewhipping, let necessity be my apology;

for the horsewhipping itself I have, unfortunately, no apology, save

the blind fury that obsessed me - which is no apology at all.

Upon the morrow I repented me already with much bitterness. But in

that hour I knew no reason. I was mad, and of my madness was born

this harsh brutality.

“You would talk of me and my affairs in a tavern, you hound!” I

cried, out of breath both by virtue of my passion and my exertions.

“Let the memory of this act as a curb upon your poisonous tongue in

future.”

“Monseigneur!” he screamed. “Misericorde, monseigneur!”

“Aye, you shall have mercy - just so much mercy as you deserve.

Have I trusted you all these years, and did my father trust you

before me, for this? Have you grown sleek and fat and smug in my

service that you should requite me thus? Sangdieu, Rodenard! My

father had hanged you for the half of the talking that you have

done this night. You dog! You miserable knave!”

“Monseigneur,” he shrieked again, “forgive! For your sainted

mother’s sake, forgive! Monseigneur, I did not know—”

“But you are learning, cur; you are learning by the pain of your

fat carcase; is it not so, carrion?”

He sank down, his strength exhausted, a limp, moaning, bleeding

mass of flesh, into which my whip still cut relentlessly.

I have a picture m my mind of that ill-lighted room, of the startled

faces on which the flickering glimmer of the candles shed odd

shadows; of the humming and cracking of my whip; of my own voice

raised in oaths and epithets of contempt; of Rodenard’s screams; of

the cries raised here and there in remonstrance or in entreaty, and

of some more bold that called shame upon me. Then others took up

that cry of “Shame!” so that at last I paused and stood there drawn

up to my full height, as if in challenge. Towering above the heads

of any in that room, I held my whip menacingly. I was unused to

criticism, and their expressions of condemnation roused me.

“Who questions my right?” I demanded arrogantly, whereupon they one

and all fell silent. “If any here be bold enough to step out, he

shall have my answer.” Then, as none responded, I signified my

contempt for them by a laugh.

“Monseigneur!” wailed Rodenard at my feet, his voice growing feeble.

By way of answer, I gave him a final cut, then I flung the whip -

which had grown ragged in the fray - back to the ostler from whom I

had borrowed it.

“Let that suffice you, Rodenard,” I said, touching him with my foot.

“See that I never set eyes upon you again, if you cherish your

miserable life!”

“Not that, monseigneur.” groaned the wretch. “Oh, not that! You

have punished me; you have whipped me until I cannot stand; forgive

me, monseigneur, forgive me now!”

“I have forgiven you, but I never wish to see you again, lest I

should forget that I have forgiven you. Take him away, some of you,”

I bade my men, and in swift, silent obedience two of them stepped

forward and bore the groaning, sobbing fellow from the room. When

that was done “Host,” I commanded, “prepare me a room. Attend

Comments (0)