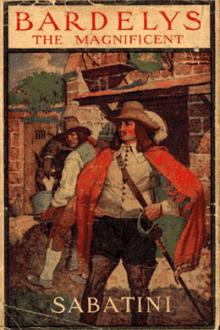

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

their head, thundered across the drawbridge, giving pause to those

within, and drawing upon themselves the eyes of all, as they rode,

two by two, under the old-world arch of the keep into the courtyard.

And Gilles, who knew our errand, and who was as ready-witted a rogue

as ever rode with me, took in the situation at a glance. Knowing

how much I desired to make a goodly show, he whispered an order.

This resulted in the couples dividing at the gateway, one going to

the left and one to the right, so that as they came they spread

themselves in a crescent, and drawing rein, they faced forward,

confronting and half surrounding the Chevalier’s company.

As each couple appeared, the curiosity - the uneasiness, probably

—of Saint-Eustache and his men, had increased, and their expectancy

was on tiptoe to see what lord it was went abroad with such regal

pomp, when I appeared in the gateway and advanced at the trot into

the middle of the quadrangle. There I drew rein and doffed my hat

to them as they stood, open-mouthed and gaping one and all. If it

was a theatrical display, a parade worthy of a tilt-ground, it was

yet a noble and imposing advent, and their gaping told me that it

was not without effect. The men looked uneasily at the Chevalier;

the Chevalier looked uneasily at his men; mademoiselle, very pale,

lowered her eyes and pressed her lips yet more tightly; the

Vicomtesse uttered an oath of astonishment; whilst Lavedan, too

dignified to manifest surprise, greeted me with a sober bow.

Behind them on the steps I caught sight of a group of domestics,

old Anatole standing slightly in advance of his fellows, and

wondering, no doubt, whether this were, indeed, the bedraggled

Lesperon of a little while ago - for if I had thought of pomp in

the display of my lacqueys, no less had I considered it in the

decking of my own person. Without any of the ribbons and fopperies

that mark the coxcomb, yet was I clad, plumed, and armed with a

magnificence such as I’ll swear had not been seen within the grey

walls of that old castle in the lifetime of any of those that were

now present.

Gilles leapt from his horse as I drew rein, and hastened to hold my

stirrup, with a murmured “Monsieur,” which title drew a fresh

astonishment into the eyes of the beholders.

I advanced leisurely towards Saint-Eustache, and addressed him with

such condescension as I might a groom, to impress and quell a man

of this type your best weapon is the arrogance that a nobler spirit

would resent.

“A world of odd meetings this, Saint-Eustache,” I smiled disdainfully.

“A world of strange comings and goings, and of range transformations.

The last time we were here we stood mutually as guests of Monsieur le

Vicomte; at present you appear to be officiating as a - a tipstaff.”

“Monsieur!” He coloured, and he uttered the word in accents of

awakening resentment. I looked into his eyes, coldly, impassively,

as if waiting to hear what he might have to add, and so I stayed

until his glance fell and his spirit was frozen in him. He knew me,

and he knew how much I was to be feared. A word from me to the King

might send him to the wheel. It was upon this I played. Presently,

as his eye fell, “Is your business with me, Monsieur de Bardelys?” he

asked, and at that utterance of my name there was a commotion on the

steps, whilst the Vicomte started, and his eyes frowned upon me, and

the Vicomtesse looked up suddenly to scan me with a fresh interest.

She beheld at last in the flesh the gentleman who had played so

notorious a part, ten years ago, in that scandal connected with the

Duchesse de Bourgogne, of which she never tired of reciting the

details. And think that she had sat at table with him day by day

and been unconscious of that momentous fact! Such, I make no doubt,

was what passed through her mind at the moment, and, to judge from

her expression, I should say that the excitement of beholding the

Magnificent Bardelys had for the nonce eclipsed beholding even her

husband’s condition and the imminent sequestration of Lavedan.

“My business is with you, Chevalier,” said I. “It relates to your

mission here.”

His jaw fell. “You wish—?”

“To desire you to withdraw your men and quit Lavedan at once,

abandoning the execution of your warrant.”

He flashed me a look of impotent hate. “You know of the existence

of my warrant, Monsieur de Bardelys, and you must therefore realize

that a royal mandate alone can exempt me from delivering Monsieur

de Lavedan to the Keeper of the Seals.”

“My only warrant,” I answered, somewhat baffled, but far from

abandoning hope, “is my word. You shall say to the Garde des Sceaux

that you have done this upon the authority of the Marquis de

Bardelys, and you have my promise that His Majesty shall confirm my

action.”

In saying that I said too much, as I was quickly to realize.

“His Majesty will confirm it, monsieur?” he said interrogatively,

and he shook his head. “That is a risk I dare not run. My warrant

sets me under imperative obligations which I must discharge - you

will see the justice of what I state.”

His tone was all humility, all subservience, nevertheless it was

firm to the point of being hard. But my last card, the card upon

which I was depending, was yet to be played.

“Will you do me the honour to step aside with me, Chevalier?” I

commanded rather than besought.

“At your service, sir,” said he; and I drew him out of earshot of

those others.

“Now, Saint-Eustache, we can talk,” said I, with an abrupt change

of manner from the coldly arrogant to the coldly menacing. “I

marvel greatly at your temerity in pursuing this Iscariot business

after learning who I am, at Toulouse two nights ago.”

He clenched his hands, and his weak face hardened.

“I would beg you to consider your expressions, monsieur, and to

control them,” said he in a thick voice.

I vouchsafed him a stare of freezing amazement. “You will no doubt

remember in what capacity I find you employed. Nay, keep your hands

still, Saint-Eustache. I don’t fight catchpolls, and if you give me

trouble my men are yonder.” And I jerked my thumb over my shoulder.

“And now to business. I am not minded to talk all day. I was saying

that I marvel at your temerity, and more particularly at your having

laid information against Monsieur de Lavedan, and having come here

to arrest him, knowing, as you must know, that I am interested in

the Vicomte.”

“I have heard of that interest, monsieur,” said he, with a sneer

for which I could have struck him.

“This act of yours,” I pursued, ignoring his interpolation, “savours

very much of flying in the face of Destiny. It almost seems to me

as if you were defying me.”

His lip trembled, and his eyes shunned my glance.

“Indeed - indeed, monsieur—” he was protesting, when I cut him

short.

“You cannot be so great a fool but that you must realize that if I

tell the King what I know of you, you will be stripped of your

ill-gotten gains, and broken on the wheel for a double traitor - a

betrayer of your fellow-rebels.”

“But you will not do that, monsieur?” he cried. “It would be

unworthy in you.”

At that I laughed in his face. “Heart of God! Are you to be what

you please, and do you still expect that men shall be nice in

dealing with you? I would do this thing, and, by my faith, Monsieur

de Eustache, I will do it, if you compel me!”

He reddened and moved his foot uneasily. Perhaps I did not take

the best way with him, after all. I might have confined myself to

sowing fear in his heart; that alone might have had the effect I

desired; by visiting upon him at the same time the insults I could

not repress, I may have aroused his resistance, and excited his

desire above all else to thwart me.

“What do you want of me?” he demanded, with a sudden arrogance which

almost cast mine into the shade.

“I want you,” said I, deeming the time ripe to make a plain tale of

it, “to withdraw your men, and to ride back to Toulouse without

Monsieur de Lavedan, there to confess to the Keeper of the Seals

that your suspicions were unfounded, and that you have culled

evidence that the Vicomte has had no relations with Monsieur the

King’s brother.”

He looked at me in amazement - amusedly, almost.

“A likely story that to bear to the astute gentlemen in Toulouse,”

said he.

“Aye, ma foi, a most likely story,” said I. “When they come to

consider the profit that you are losing by not apprehending the

Vicomte, and can think of none that you are making, they will have

little difficulty in believing you.”

“But what of this evidence you refer to?”

“You have, I take it, discovered no incriminating evidence - no

documents that will tell against the Vicomte?”

“No, monsieur, it is true that I have not—”

He stopped and bit his lip, my smile making him aware of his

indiscretion.

“Very well, then, you must invent some evidence to prove that he

was in no way, associated with the rebellion.”

“Monsieur de Bardelys,” said he very insolently, “we waste time in

idle words. If you think that I will imperil my neck for the sake

of serving you or the Vicomte, you are most prodigiously at fault.”

“I have never thought so. But I have thought that you might be

induced to imperil your neck - as you have it - for its own sake,

and to the end that you might save it.”

He moved away. “Monsieur, you talk in vain. You have no royal

warrant to supersede mine. Do what you will when you come to

Toulouse,” and he smiled darkly. “Meanwhile, the Vicomte goes with

me.”

“You have no evidence against him!” I cried, scarce believing that

he would dare to defy me and that I had failed.

“I have the evidence of my word. I am ready to swear to what I know

—that, whilst I was here at Lavedan, some weeks ago, I discovered

his connection with the rebels.”

“And what think you, miserable fool, shall your word weigh against

mine?” I cried. “Never fear, Monsieur le Chevalier, I shall be in

Toulouse to give you the lie by showing that your word is a word to

which no man may attach faith, and by exposing to the King your past

conduct. If you think that, after I have spoken, King Louis whom

they name the just will suffer the trial of the Vicomte to go further

on your instigation, or if you think that you will be able to slip

your own neck from the noose I shall have set about it, you are an

infinitely greater fool than I deem you.”

He stood and looked at me over his shoulder, his face crimson, and

his brows black as a thundercloud.

“All this may betide when you come to Toulouse, Monsieur de

Bardelys,” said he darkly, “but from here to Toulouse it is a matter

of some twenty leagues.”

With

Comments (0)