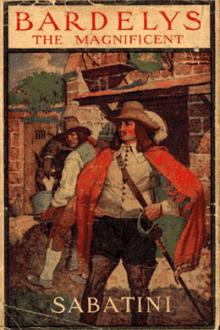

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

a couple of you.”

I gave orders thereafter for the disposal of my baggage, some of

which my lacqueys brought up to the chamber that the landlord had

in haste made ready for me. In that chamber I sat until very late;

a prey to the utmost misery and despair. My rage being spent, I

might have taken some thought for poor Ganymede and his condition,

but my own affairs crowded over-heavily upon my mind, and sat the

undisputed rulers of my thoughts that night.

At one moment I considered journeying to Lavedan, only to dismiss

the idea the next. What could it avail me now? Would Roxalanne

believe the tale I had to tell? Would she not think, naturally

enough, that I was but making the best of the situation, and that

my avowal of the truth of a story which it was not in my power to

deny was not spontaneous, but forced from me by circumstances? No,

there was nothing more to be done. A score of amours had claimed

my attention in the past and received it; yet there was not one of

those affairs whose miscarriage would have afforded me the slightest

concern or mortification. It seemed like an irony, like a Dies ire,

that it should have been left to this first true passion of my life

to have gone awry.

I slept ill when at last I sought my bed, and through the night I

nursed my bitter grief, huddling to me the corpse of the love she

had borne me as a mother may the corpse of her first-born.

On the morrow I resolved to leave Toulouse - to quit this province

wherein so much had befallen me and repair to Beaugency, there to

grow old in misanthropical seclusion. I had done with Courts, I

had done with love and with women; I had done, it seemed to me, with

life itself. Prodigal had it been in gifts that I had not sought of

it. It had spread my table with the richest offerings, but they had

been little to my palate, and I had nauseated quickly. And now,

when here in this remote corner of France it had shown me the one

prize I coveted, it had been swift to place it beyond my reach,

thereby sowing everlasting discontent and misery in my hitherto

pampered heart.

I saw Castelroux that day, but I said no word to him of my

affliction. He brought me news of Chatellerault. The Count was

lying in a dangerous condition at the Auberge Royale, and might not

be moved. The physician attending him all but despaired of his life.

“He is asking to see you,” said Castelroux.

But I was not minded to respond. For all that he had deeply wronged

me, for all that I despised him very cordially, the sight of him

in his present condition might arouse my pity, and I was in no mood

to waste upon such a one as Chatellerault even on his deathbed - a

quality of which I had so dire a need just then for my own case.

“I will not go,” said I, after deliberation. “Tell him from me that

I forgive him freely if it be that he seeks my forgiveness; tell

him that I bear him no rancour, and - that he had better make his

will, to save me trouble hereafter, if he should chance to die.”

I said this because I had no mind, if he should perish intestate, to

go in quest of his next heirs and advise them that my late Picardy

estates were now their property.

Castelroux sought yet to persuade me to visit the Count, but I held

firmly to my resolve.

“I am leaving Toulouse to-day,” I announced.

“Whither do you go?”

“To hell, or to Beaugency - I scarce know which, nor does it matter.”

He looked at me in surprise, but, being a man of breeding, asked no

questions upon matters that he accounted secret.

“But the King?” he ventured presently.

“His Majesty has already dispensed me from my duties by him.”

Nevertheless, I did not go that day. I maintained the intention

until sunset; then, seeing that it was too late, I postponed my

departure until the morrow. I can assign no reason for my dallying

mood. Perhaps it sprang from the inertness that pervaded me,

perhaps some mysterious hand detained me. Be that as it may, that

I remained another night at the Hotel de l’Epee was one of those

contingencies which, though slight and seemingly inconsequential

in themselves, lead to great issues. Had I departed that day for

Beaugency, it is likely that you had never heard of me - leastways,

not from my own pen - for in what so far I have told you, without

that which is to follow, there is haply little that was worth the

labour of setting down.

In the morning, then, I set out; but having started late, we got

no farther than Grenade, where we lay the night once more at the

Hotel de la Couronne. And so, through having delayed my departure

by a single day, did it come to pass that a message reached me

before it might have been too late.

It was high noon of the morrow. Our horses stood saddled; indeed,

some of my men were already mounted - for I was not minded to

disband them until Beaugency was reached - and my two coaches were

both ready for the journey. The habits of a lifetime are not so

easy to abandon even when Necessity raises her compelling voice.

I was in the act of settling my score with the landlord when of a

sudden there were quick steps in the passage, the clank of a rapier

against the wall, and a voice - the voice of Castelroux - calling

excitedly “Bardelys! Monsieur de Bardelys!”

“What brings you here?” I cried in greeting, as he stepped into

the room.

“Are you still for Beaugency?” he asked sharply, throwing back his

head.

“Why, yes,” I answered, wondering at this excitement.

“Then you have seen nothing of Saint-Eustache and his men?”

“Nothing.”

“Yet they must have passed this way not many hours ago.” Then

tossing his hat on the table and speaking with sudden vehemence:

“If you have any interest in the family of Lavedan, you will return

upon the instant to Toulouse.”

The mention of Lavedan was enough to quicken my pulses. Yet in the

past two days I had mastered resignation, and in doing that we

school ourselves to much restraint. I turned slowly, and surveyed

the little Captain attentively. His black eyes sparkled, and his

moustaches bristled with excitement. Clearly he had news of import.

I turned to the landlord.

“Leave us, Monsieur l’Hote,” said I shortly; and when he had

departed, “What of the Lavedan family, Castelroux?” I inquired as

calmly as I might.

“The Chevalier de Saint-Eustache left Toulouse at six o’clock this

morning for Lavedan.”

Swift the suspicion of his errand broke upon my mind.

“He has betrayed the Vicomte?” I half inquired, half asserted.

Castelroux nodded. “He has obtained a warrant for his apprehension

from the Keeper of the Seals, and is gone to execute it. In the

course of a few days Lavedan will be in danger of being no more

than a name. This Saint-Eustache is driving a brisk trade, by God,

and some fine prizes have already fallen to his lot. But if you

add them all together, they are not likely to yield as much as this

his latest expedition. Unless you intervene, Bardelys, the Vicomte

de Lavedan is doomed and his family houseless.”

“I will intervene,” I cried. “By God, I will! And as for

Saint-Eustache - he was born under a propitious star, indeed, if

he escapes the gallows. He little dreams that I am still to be

reckoned with. There, Castelroux, I will start for Lavedan at once.”

Already I was striding to the door, when the Gascon called me back.

“What good will that do?” he asked. “Were it not better first to

return to Toulouse and obtain a counter-warrant from the King?”

There was wisdom in his words - much wisdom. But my blood was afire,

and I was in too hot a haste to reason.

“Return to Toulouse?” I echoed scornfully. “A waste of time, Captain.

No, I will go straight to Lavedan. I need no counter-warrant. I

know too much of this Chevalier’s affairs, and my very presence should

be enough to stay his hand. He is as foul a traitor as you’ll find in

France; but for the moment God bless him for a very opportune knave.

Gilles!” I called, throwing wide the door. “Gilles!”

“Monseigneur,” he answered, hastening to me.

“Put back the carriages and saddle me a horse,” I commanded. “And

bid your fellows mount at once and await me in the courtyard. We

are not going to Beaugency, Gilles. We ride north - to Lavedan.”

SAINT-EUSTACHE IS OBSTINATE

0n the occasion of my first visit to Lavedan I had disregarded - or,

rather, Fate had contrived that I should disregard - Chatellerault’s

suggestion that I should go with all the panoply of power - with my

followers, my liveries, and my equipages to compose the magnificence

all France had come to associate with my name, and thus dazzle by

my brilliant lustre the lady I was come to win. As you may remember,

I had crept into the chateau like a thief in the night, - wounded,

bedraggled, and of miserable aspect, seeking to provoke compassion

rather than admiration.

Not so now that I made my second visit. I availed myself of all

the splendour to which I owed my title of “Magnificent,” and rode

into the courtyard of the Chateau de Lavedan preceded by twenty

well-mounted knaves wearing the gorgeous Saint-Pol liveries of

scarlet and gold, with the Bardelys escutcheon broidered on the

breasts of their doublets - on a field or a bar azure surcharged by

three lilies of the field. They were armed with swords and

musketoons, and had more the air of a royal bodyguard than of a

company of attendant servants.

Our coming was in a way well timed. I doubt if we could have

stayed the execution of Saint-Eustache’s warrant even had we arrived

earlier. But for effect - to produce a striking coup de theatre -

we could not have come more opportunely.

A coach stood in the quadrangle, at the foot of the chateau steps:

down these the Vicomte was descending, with the Vicomtesse - grim

and blasphemant as ever, on one side, and his daughter, white of

face and with tightly compressed lips, on the other. Between these

two women - his wife and his child - as different in body as they

were different in soul, came Lavedan with a firm step, a good colour,

and a look of well-bred, lofty indifference to his fate.

He disposed himself to enter the carriage which was to bear him to

prison with much the same air he would have assumed had his

destination been a royal levee.

Around the coach were grouped a score of men of Saint-Eustache’s

company - half soldiers, half ploughboys - ill-garbed and

indifferently accoutred in dull breastplates and steel caps, many

of which were rusted. By the carriage door stood the long, lank

figure of the Chevalier himself, dressed with his wonted care, and

perfumed, curled, and beribboned beyond belief. His weak, boyish

face sought by scowls and by the adoption of a grim smile to assume

an air of martial ferocity.

Such

Comments (0)