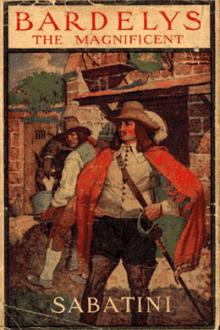

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

imminence of the peril had been such that, as we mutually recovered,

I found a cold sweat bathing me.

After that, I resolved to abandon the attempt to disarm him by

pressure, and I turned my attention to drawing him into a position

that might lend itself to seizure. But even as I was making up my

mind to this - we were engaged in sixte at the time - I saw a sudden

chance. His point was held low while he watched me; so low that his

arm was uncovered and my point was in line with it. To see the

opening, to estimate it, and to take my resolve was all the work of

a fraction of a second. The next instant I had straightened my elbow,

my blade shot out in a lightning stroke and transfixed his sword-arm.

There was a yell of pain, followed by a deep growl of fury, as,

wounded but not vanquished, the enraged Count caught his falling

sword in his left hand, and whilst my own blade was held tight in

the bone of his right arm, he sought to run me through. I leapt

quickly aside, and then, before he could renew the attempt, my

friends had fallen upon him and wrenched his sword from his hand

and mine from his arm.

It would ill have become me to taunt a man in his sorry condition,

else might I now have explained to him what I had meant when I had

promised to leave him for the headsman even though I did consent to

fight him.

Mironsac, Castelroux, and La Fosse stood babbling around me, but I

paid no heed either to Castelroux’s patois or to La Fosse’s

misquotations of classic authors. The combat had been protracted,

and the methods I had pursued had been of a very exhausting nature.

I leaned now against the portecochere, and mopped myself vigorously.

Then Saint-Eustache, who was engaged in binding up his principal’s

arm, called to La Fosse.

I followed my second with my eyes as he went across to Chatellerault.

The Count stood white, his lips compressed, no doubt from the pain

his arm was causing him. Then his voice floated across to me as he

addressed La Fosse.

“You will do me the favour, monsieur, to inform your friend that

this was no first blood combat, but one a outrance. I fence as well

with my left arm as with my right, and if Monsieur de Bardelys will

do me the honour to engage again, I shall esteem it.”

La Fosse bowed and came over with the message that already we had

heard.

“I fought,” said I in answer, “in a spirit very different from that

by which Monsieur de Chatellerault appears to have been actuated.

He made it incumbent upon me to afford proof of my courage. That

proof I have afforded; I decline to do more. Moreover, as Monsieur

de Chatellerault himself must perceive, the light is failing us, and

in a few minutes it will be too dark for swordplay.”

“In a few minutes there will be need for none, monsieur,” shouted

Chatellerault, to save time. He was boastful to the end.

“Here, monsieur, in any case, come those who will resolve the

question,” I answered, pointing to the door of the inn.

As I spoke, the landlord stepped into the yard, followed by an

officer and a half-dozen soldiers. These were no ordinary keepers of

the peace, but musketeers of the guard, and at sight of them I knew

that their business was not to interrupt a duel, but to arrest my

erstwhile opponent upon a much graver charge.

The officer advanced straight to Chatellerault.

“In the King’s name, Monsieur le Comte,” said he. “I demand your

sword.”

It may be that at bottom I was still a man of soft heart, unfeeling

cynic though they accounted me; for upon remarking the misery and

gloom that spread upon Chatellerault’s face I was sorry for him,

notwithstanding the much that he had schemed against me. Of what

his fate would be he could have no shadow of doubt. He knew - none

better - how truly the King loved me, and how he would punish such

an attempt as had been made upon my life, to say nothing of the

prostitution of justice of which he had been guilty, and for which

alone he had earned the penalty of death.

He stood a moment with bent head, the pain of his arm possibly

forgotten in the agony of his spirit. Then, straightening himself

suddenly, with a proud, half scornful air, he looked the officer

straight between the eyes.

“You desire my sword, monsieur?” he inquired.

The musketeer bowed respectfully.

“Saint-Eustache, will you do me the favour to give it to me?”

And while the Chevalier picked up the rapier from the ground where

it had been flung, that man waited with an outward calm for which

at the moment I admired him, as we must ever admire a tranquil

bearing in one smitten by a great adversity. And than this I can

conceive few greater. He had played for much, and he had lost

everything. Ignominy, degradation, and the block were all that

impended for him in this world, and they were very imminent.

He took the sword from the Chevalier. He held it for a second by

the hilt, like one in thought, like one who is resolving upon

something, whilst the musketeer awaited his good pleasure with that

deference which all gentle minds must accord to the unfortunate.

Still holding his rapier, he raised his eyes for a second and let

them rest on me with a grim malevolence. Then he uttered a short

laugh, and, shrugging his shoulders, he transferred his grip to the

blade, as if about to offer the hilt to the officer. Holding it so,

halfway betwixt point and quillons, he stepped suddenly back, and

before any there could put forth a hand to stay him, he had set the

pummel on the ground and the point at his breast, and so dropped

upon it and impaled himself.

A cry went up from every throat, and we sprang towards him. He

rolled over on his side, and with a grin of exquisite pain, yet in

words of unconquerable derision “You may have my sword now, Monsieur

l’Officier,” he said, and sank back, swooning.

With an oath, the musketeer stepped forward. He obeyed Chatellerault

to the letter, by kneeling beside him and carefully withdrawing the

sword. Then he ordered a couple of his men to take up the body.

“Is he dead?” asked some one; and some one else replied, “Not yet,

but he soon will be.”

Two of the musketeers bore him into the inn and laid him on the floor

of the very room in which, an hour or so ago, he had driven a bargain

with Roxalanne. A cloak rolled into a pillow was thrust under his

head, and there we left him in charge of his captors, the landlord,

Saint-Eustache, and La Fosse the latter inspired, I doubt not, by

that morbidity which is so often a feature of the poetic mind, and

which impelled him now to witness the death-agony of my Lord of

Chatellerault.

Myself, having resumed my garments, I disposed myself to repair at

once to the Hotel de l’Epee, there to seek Roxalanne, that I might

set her fears and sorrows at rest, and that I might at last make my

confession.

As we stepped out into the street, where the dusk was now thickening,

I turned to Castelroux to inquire how Saint-Eustache came into

Chatellerault’s company.

“He is of the family of the Iscariot, I should opine,” answered the

Gascon. “As soon as he had news that Chatellerault was come to

Languedoc as the King’s Commissioner, he repaired to him to offer

his services in the work of bringing rebels to justice. He urged

that his thorough acquaintance with the province should render him

of value to the King, as also that he had had particular opportunities

of becoming acquainted with many treasonable dealings on the part

of men whom the State was far from suspecting.”

“Mort Dieu!” I cried, “I had suspected something of such a nature.

You do well to call him of the family of the Iscariot. He is more

so than you imagine: I have knowledge of this - ample knowledge. He

was until lately a rebel himself, and himself a follower of Gaston

d’Orleans - though of a lukewarm quality. What reasons have driven

him to such work, do you know?”

“The same reason that impelled his forefather, Judas of old. The

desire to enrich himself. For every hitherto unsuspected rebel that

shall be brought to justice and whose treason shall be proven by his

agency, he claims the half of that rebel’s confiscated estates.”

“Diable!” I exclaimed. “And does the Keeper of the Seals sanction

this?”

“Sanction it? Saint-Eustache holds a commission, has a free hand

and a company of horse to follow him in his rebel-hunting.”

“Has he done much so far?” was my next question.

“He has reduced half a dozen noblemen and their families. The wealth

he must thereby have amassed should be very considerable, indeed.”

“Tomorrow, Castelroux, I will see the King in connection with this

pretty gentleman, and not only shall we find him a dungeon deep and

dank, but we shall see that he disgorges his blood-money.”

“If you can prove his treason you will be doing blessed work,”

returned Castelroux. “Until tomorrow, then, for here is the Hotel

de l’Epee.”

From the broad doorway of an imposing building a warm glow of light

issued out and spread itself fanwise across the ill-paved street.

In this - like bats about a lamp - flitted the black figures of

gaping urchins and other stragglers, and into this I now passed,

having taken leave of my companions.

I mounted the steps and I was about to cross the threshold, when

suddenly above a burst of laughter that greeted my ears I caught the

sound of a singularly familiar voice. This seemed raised at present

to address such company as might be within. One moment of doubt had

I - for it was a month since last I had heard those soft, unctuous

accents. Then I was assured that the voice I heard was, indeed, the

voice of my steward Ganymede. Castelroux’s messenger had found him

at last, it seemed, and had brought him to Toulouse.

I was moved to spring into the room and greet that old retainer for

whom, despite the gross and sensuous ways that with advancing years

were claiming him more and more, I had a deep attachment. But even

as I was on the point of entering, not only his voice, but the very

words that he was uttering floated out to my ears, and they were of

a quality that held me there to play the hidden listener for the

second time in my life in one and the same day.

THE BABBLING OF GANYMEDE

Never until that hour, as I stood in the porch of the Hotel de

l’Epee, hearkening to my henchman’s narrative and to the bursts of

laughter which ever and anon it provoked from his numerous

listeners, had I dreamed of the raconteur talents which Rodenard

might boast. Yet was I very far from being appreciative now that

I discovered them, for the story that he told was of how one Marcel

Saint-Pol, Marquis de Bardelys, had laid a wager with the Comte de

Chatellerault that he would woo and win Mademoiselle de Lavedan to

wife within three months.

Comments (0)