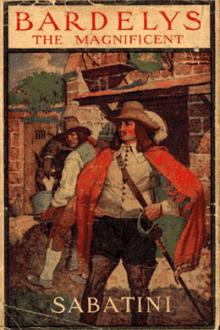

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

puzzle out the inner meaning of his parting words.

He gave his men the order to mount, and bade Monsieur de Lavedan

enter the coach, whereupon Gilles shot me a glance of inquiry. For

a second, as I stepped slowly after the Chevalier, I was minded to

try armed resistance, and to convert that grey courtyard into a

shambles. Then I saw betimes the futility of such a step, and I

shrugged my shoulders in answer to my servant’s glance.

I would have spoken to the Vicomte ere he departed, but I was too

deeply chagrined and humiliated by my defeat. So much so that I

had no room in my thoughts even for the very natural conjecture of

what Lavedan must be thinking of me. I repented me then of my

rashness in coming to Lavedan without having seen the King - as

Castelroux had counselled me. I had come indulging vain dreams of

a splendid overthrow of Saint-Eustache. I had thought to shine

heroically in Mademoiselle’s eyes, and thus I had hoped that both

gratitude for having saved her father and admiration at the manner

in which I had achieved it would predispose her to grant me a hearing

in which I might plead my rehabilitation. Once that were accorded

me, I did not doubt I should prevail.

Now my dream was all dispelled, and my pride had suffered just such

a humiliating fall as the moralists tell us pride must ever suffer.

There seemed little left me but to go hence with lambent tail, like

a dog that has been whipped - my dazzling escort become a mockery

but that it served the more loudly to advertise my true impotency.

As I approached the carriage, the Vicomtesse swept suddenly down

the steps and came towards me with a friendly smile. “Monsieur de

Bardelys,” said she, “we are grateful for your intervention in the

cause of that rebel my husband.”

“Madame,” I besought her, under my breath, “if you would not totally

destroy him, I beseech you to be cautious. By your leave, I will

have my men refreshed, and thereafter I shall take the road to

Toulouse again. I can only hope that my intervention with the King

may bear better fruit.”

Although I spoke in a subdued key, Saint-Eustache, who stood near

us, overheard me, as his face very clearly testified.

“Remain here, sir,” she replied, with some effusion, “and follow us

when you are rested.”

“Follow you?” I inquired. “Do you then go with Monsieur de Lavedan?”

“No, Anne,” said the Vicomte politely from the carriage. “It will

be tiring you unnecessarily. You were better advised to remain

here until my return.”

I doubt not that the poor Vicomte was more concerned with how she

would tire him than with how the journey might tire her. But the

Vicomtesse was not to be gainsaid. The Chevalier had sneered when

the Vicomte spoke of returning. Madame had caught that sneer, and

she swung round upon him now with the vehement fury of a virago.

“He’ll not return, you think, you Judas!” she snarled at him, her

lean, swarthy face growing very evil to see. “But he shall - by God,

he shall! And look to your skin when he does, monsieur the catchpoll,

for, on my honour, you shall have a foretaste of hell for your

trouble in this matter.”

The Chevalier smiled with much restraint. “A woman’s tongue,” said

he, “does no injury.”

“Will a woman’s arm, think you?” demanded that warlike matron. “You

musk-stinking tipstaff, I’ll—”

“Anne, my love,” implored the Vicomte soothingly, “I beg that you

will control yourself.”

“Shall I submit to the insolence of this misbegotten vassal? Shall

I—”

“Remember rather that it does not become the dignity of your station

to address the fellow. We avoid venomous reptiles, but we do not

pause to reproach them with their venom. God made them so.”

Saint-Eustache coloured to the roots of his hair, then, turning

hastily to the driver, he bade him start. He would have closed the

door with that, but that madame thrust herself forward.

That was the Chevalier’s chance to be avenged. “You cannot go,”

said he.

“Cannot?” Her cheeks reddened. “Why not, monsieur Lesperon?

“I have no reasons to afford you,” he answered brutally. “You

cannot go.”

“Your pardon, Chevalier,” I interposed. “You go beyond your rights

in seeking to prevent her. Monsieur le Vicomte is not yet convicted.

Do not, I beseech you, transcend the already odious character of your

work.”

And without more ado I shouldered him aside, and held the door that

she might enter. She rewarded me with a smile—half vicious, half

whimsical, and mounted the step. Saint-Eustache would have

interfered. He came at me as if resenting that shoulder-thrust of

mine, and for a second I almost thought he would have committed the

madness of striking me.

“Take care, Saint-Eustache,” I said very quietly, my eyes fixed on

his. And much as dead Caesar’s ghost may have threatened Brutus

with Philippi “We meet at Toulouse, Chevalier,” said I, and closing

the carriage door I stepped back.

There was a flutter of skirts behind me. It was mademoiselle. So

brave and outwardly so calm until now, the moment of actual

separation - and added thereunto perhaps her mother’s going and the

loneliness that for herself she foresaw - proved more than she could

endure. I stepped aside, and she swept past me and caught at the

leather curtain of the coach.

“Father!” she sobbed.

There are some things that a man of breeding may not witness - some

things to look upon which is near akin to eavesdropping or reading

the letters of another. Such a scene did I now account the present

one, and, turning, I moved away. But Saint-Eustache cut it short,

for scarce had I taken three paces when his voice rang out the

command to move. The driver hesitated, for the girl was still

hanging at the window. But a second command, accompanied by a

vigorous oath, overcame his hesitation. He gathered up his reins,

cracked his whip, and the lumbering wheels began to move.

“Have a care, child!” I heard the Vicomte cry, “have a care! Adieu,

mon enfant!”

She sprang back, sobbing, and assuredly she would have fallen, thrown

out of balance by the movement of the coach, but that I put forth my

hands and caught her.

I do not think she knew whose were the arms that held her for that

brief space, so desolated was she by the grief so long repressed.

At last she realized that it was this worthless Bardelys against

whom she rested; this man who had wagered that he would win and wed

her; this impostor who had come to her under an assumed name; this

knave who had lied to her as no gentleman could have lied, swearing

to love her, whilst, in reality, he did no more than seek to win a

wager. When all this she realized, she shuddered a second, then

moved abruptly from my grasp, and, without so much as a glance at

me, she left me, and, ascending the steps of the chateau, she passed

from my sight.

I gave the order to dismount as the last of Saint-Eustache’s

followers vanished under the portcullis.

THE FLINT AND THE STEEL

Mademoiselle will see you, monsieur,” said Anatole at last.

Twice already had he carried unavailingly my request that Roxalanne

should accord me an interview ere I departed. On this the third

occasion I had bidden him say that I would not stir from Lavedan

until she had done me the honour of hearing me. Seemingly that

threat had prevailed where entreaties had been scorned.

I followed Anatole from the half-light of the hall in which I had

been pacing into the salon overlooking the terraces and the river,

where Roxalanne awaited me. She was standing at the farther end of

the room by one of the long windows, which was open, for, although

we were already in the first week of October, the air of Languedoc

was as warm and balmy as that of Paris or Picardy is in summer.

I advanced to the centre of the chamber, and there I paused and

waited until it should please her to acknowledge my presence and

turn to face me. I was no fledgling. I had seen much, I had learnt

much and been in many places, and my bearing was wont to convey it.

Never in my life had I been gauche, for which I thank my parents,

and if years ago - long years ago - a certain timidity had marked my

first introductions to the Louvre and the Luxembourg, that timidity

was something from which I had long since parted company. And yet

it seemed to me, as I stood in that pretty, sunlit room awaiting the

pleasure of that child, scarce out of her teens, that some of the

awkwardness I had escaped in earlier years, some of the timidity of

long ago, came to me then. I shifted the weight of my body from one

leg to the other; I fingered the table by which I stood; I pulled at

the hat I held; my colour came and went; I looked at her furtively

from under bent brows, and I thanked God that her back being towards

me she might not see the clown I must have seemed.

At length, unable longer to brook that discomposing silence—

“Mademoiselle!” I called softly. The sound of my own voice seemed to

invigorate me, to strip me of my awkwardness and self-consciousness.

It broke the spell that for a moment had been over me, and brought me

back to myself - to the vain, self-confident, flamboyant Bardelys that

perhaps you have pictured from my writings.

“I hope, monsieur,” she answered, without turning, “that what you

may have to say may justify in some measure your very importunate

insistence.”

On my life, this was not encouraging. But now that I was master of

myself, I was not again so easily to be disconcerted. My eyes

rested upon her as she stood almost framed in the opening of that

long window. How straight and supple she was, yet how dainty and

slight withal! She was far from being a tall woman, but her clean

length of limb, her very slightness, and the high-bred poise of her

shapely head, conveyed an illusion of height unless you stood beside

her. The illusion did not sway me then. I saw only a child; but a

child with a great spirit, with a great soul that seemed to

accentuate her physical helplessness. That helplessness, which I

felt rather than saw, wove into the warp of my love. She was in

grief just then - in grief at the arrest of her father, and at the

dark fate that threatened him; in grief at the unworthiness of a

lover. Of the two which might be the more bitter it was not mine

to judge, but I burned to gather her to me, to comfort and cherish

her, to make her one with me, and thus, whilst giving her something

of my man’s height and strength, cull from her something of that

pure, noble spirit, and thus sanctify my own.

I had a moment’s weakness when she spoke. I was within an ace of

advancing and casting myself upon my knees like any Lenten penitent,

to sue forgiveness. But I set the inclination down betimes. Such

expedients would not avail me here.

“What I have to say, mademoiselle,” I answered after a pause, “would

justify a

Comments (0)